Tourism is one of Montana’s leading industries, creating thousands of jobs and contributing billions of dollars to our state’s economy annually.[1] Tourism activities in Indian Country continue to grow and represent a significant opportunity to expand economic development on reservations and across the state.

Senate Bill 309 would help increase tourism in Indian Country and Montana by: (1) creating a specific Indian Country Tourism Region from within the state’s existing tourism regions; (2) designating one existing member of the Governor’s Tourism Advisory Council (TAC) to be a tribal member from the private sector; and (3) recognizing the State Tribal Economic Development Commission as the point of contact to work collaboratively with TAC to expand tourism in Indian Country. Altogether, these minor but important changes will help tribes and the state maximize the benefits of tourism in Montana.

In 2015, 11.7 million people visited Montana, spending $3.66 billion and contributing an estimated $5.15 billion to the overall Montana economy in the form of direct, indirect, and induced spending.[2]

52,630 Jobs

$4.8 Billion in Goods & Services

$194 Million in State & Local Taxes

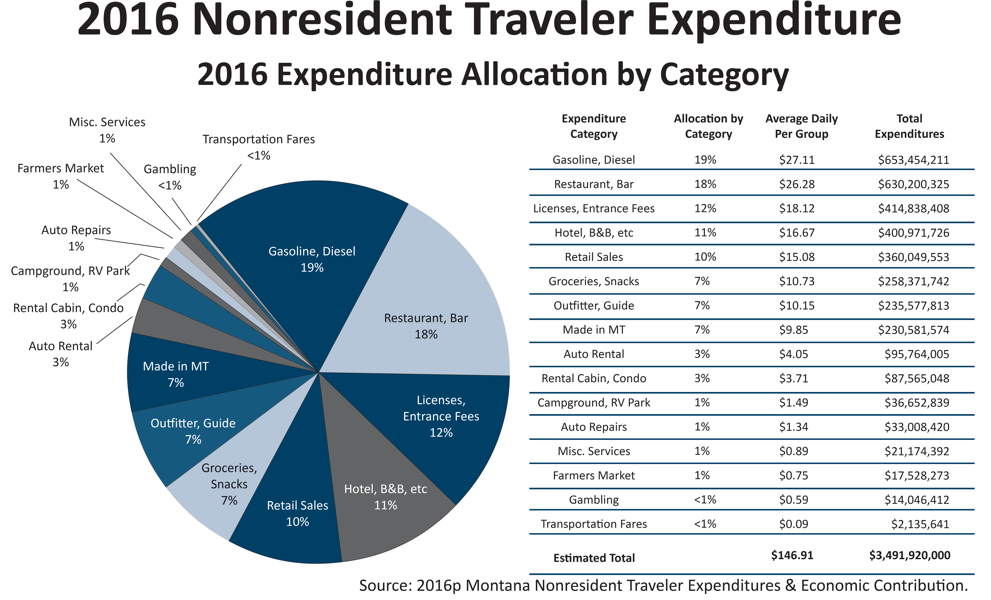

Businesses like gas stations, restaurants, hotels, and retail stores most directly benefit from tourism. In 2016, tourists spent the greatest share of their dollars on gasoline/diesel. Restaurants and bars saw the second greatest share, followed by licenses and entrance fees, and then sleeping accommodations.[5] A preliminary breakdown of tourist spending by category for 2016 is reflected in the chart on the following page.

Data compiled for 2013 shows the highest-spending visitors to Montana were those who came to participate in outdoor recreational activities. These visitors tended to stay for about ten days, almost twice as long as all other visitors, and on average spent $293 per day.[6] In 2015, high-spenders stayed for six nights and spent an average of $351 per day.[7]

Research indicates that consistently the main attractant for visitors to Montana is outdoor recreation, with the primary draws being Glacier National Park and Yellowstone Park. This is followed by recreation in mountains, forests, and open spaces outside of the parks.[8]

In 2016, the most popular activities visitors engaged in were, in the following order: day hiking, wildlife watching, nature photography, fishing, birding, river rafting, road/mountain biking, skiing, and horseback riding.[9]

Data for 2012-2014 shows that thirteen percent of visitors to Montana came to experience American Indian history and culture.[10] This means that between 2012-2014, a total of approximately 4.2 million visitors—or 1.4 million visitors annually—were drawn to Montana for reasons directly related to American Indians.[11] This is a sizeable number that could increase with focus and investment, thereby benefitting Indian Country and the rest of the state—because what is good for Indian Country is good for Montana.

In a comprehensive 2016 study of more than 6,200 leisure travelers representing 300 national and international key markets feeding into the Montana tourism industry, 46.5 percent of respondents reported that they would be interested in coming to Montana to visit American Indian historical or cultural sites.[12] Expected spending by this group of respondents ranked sixth, coming in above segments visiting Lewis and Clark-related historical sites, Glacier and Yellowstone National Parks, and geological/dinosaur-related historical sites. Furthermore, 35 percent of respondents rated “Historical attractions” as an “Extremely important” attribute in selecting travel destinations. This “history buff” segment represents over a third of the overall population of Montana’s tourism target market.[13]

Senate Bill 309 would help bridge the gap in developing this promising niche market and bringing more of these travelers into our state.

Focus and Investment in Indian Country Tourism

Senate Bill 309 aims to increase tourism in Indian Country and Montana. Many tribes are seeking to diversify from single-revenue generating assets like agriculture, coal, or timber to include more emphasis on tourism. From hotels, campgrounds, gas stations, guided hunts, and exhibitions of traditional culture, several tribes have already undertaken a variety of economic development efforts focused on tourism and others are planning to do more in the future.

In addition to the efforts and enterprises undertaken by tribal governments there are also several individual Indian-owned businesses working to draw visitors to their communities. These businesses offer an array of products and services including activities like white water rafting, overnight camping in tipis and cabins, and guided cultural tours of tribal homelands.

Senate Bill 309 would help maximize the benefits of tourism to enhance reservation economies by supporting the growth of local businesses and increasing employment opportunities.

SB 309 focuses on Indian Country by creating a specific Indian Country Tourism Region from within the state’s existing tourism regions. Unquestionably, local tribal members, governments, and business owners are in the best position to understand and identify the unique local landscapes, cultures, recreational opportunities, and events that will help increase tourism in their communities.

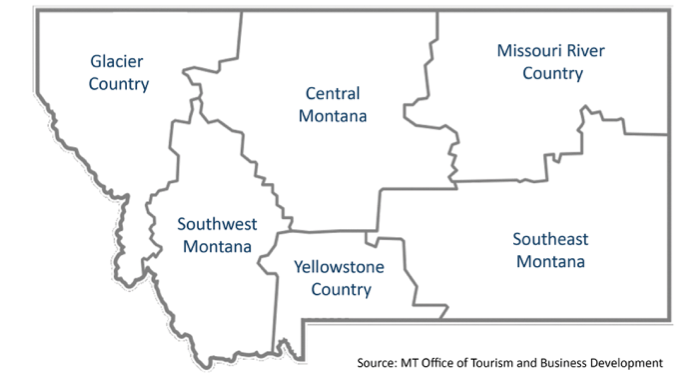

SB 309 also designates one member of the Governor’s twelve-seat Tourism Advisory Council (TAC) to be a tribal member from the private sector. Currently, the state of Montana is divided into six tourism regions: Glacier Country, Central Montana, Missouri River Country, Southeast Montana, Yellowstone Country, and Southwest Montana. Private sector travel industry representatives from each tourism region serve on TAC, with at least one member being from among tribal governments.[14]

Privately owned businesses and tribal government-run enterprises differ in function and aim. The addition of a tribal member business owner on a board comprised of other private sector experts in their respective fields is important in balancing and complementing the perspective of the tribal government official.

Perhaps most importantly, SB 309 would task the State Tribal Economic Development (STED) Commission to work in conjunction with TAC to oversee the use of proceeds to expand tourism activities in Indian Country. This is a natural pairing, as both the STED Commission and TAC are partnering organizations within the Montana Office of Tourism and Business Development.[15] Furthermore, the STED Commission is responsible for assisting, promoting, developing, and proposing recommendations for accelerating on-reservation economic development.

Because the STED Commission is comprised of eleven representatives from the eight tribal governments in Montana, it is intimately familiar with the most promising existing and prospective economic development projects in Indian Country, including those related to tourism. Therefore, the STED Commission is ideally positioned to lead the charge in working collaboratively with TAC to successfully expand tourism in Indian Country.

SB 309 is Good for Indian Country Tourism, Good for Montana

Ultimately, the three minor but impactful proposals in SB 309 will allow for a more focused and collaborative approach to increasing tourism in Indian Country and Montana.

MBPC is a nonprofit organization focused on providing credible and timely research and analysis on budget, tax, and economic issues that impact low- and moderate-income Montana families.