Child care is an essential part of our economy, enabling families to work while preparing children for school and employing a large workforce. Unfortunately, the coronavirus public health crisis has exacerbated the challenges that decades of underinvestment have produced in the child care system. Montana has a large population of working parents with young children who need child care to work. Prior to the pandemic, the Montana child care system served only half of children needing care, and the number of providers had decreased in the previous decade. While finding affordable child care is tough for families across the state, for those living on lower incomes it is even more pronounced as many are unable to afford to work and pay for child care. Meanwhile, on average child care workers are underpaid, lack employer-sponsored health insurance, and many are on the frontlines of the pandemic providing care for our children.[1]

Montana went into this pandemic with inadequate support for the child care industry and now child care in this state stands at a crossroads. Montana lawmakers can decide to improve the long-standing issues with our child care system, supporting families and workers, or ignore the realities of this pandemic and allow the child care system to suffer, leaving many families without care for the foreseeable future and further weakening our economy.

Young Children in Montana

Out of just over a million people in Montana, approximately a quarter (229,434) are under the age of 18 and 62,536 are under the age of five.[2] Children are more likely than adults to live in households with low incomes. Nearly one out of every five children under age 5 (about 18 percent) are living in poverty, as opposed to 13 percent of the total Montana population.

Due to historical oppression, inequitable public policies, and present-day discrimination that create barriers to economic security, American Indians living in Montana are much more likely to live in households with incomes below the federal poverty level. Over one-third (34.8 percent) of American Indians live in households with low incomes, and 10 percent of Montana children are American Indian.[3],[4]

Child Care Workers in Montana

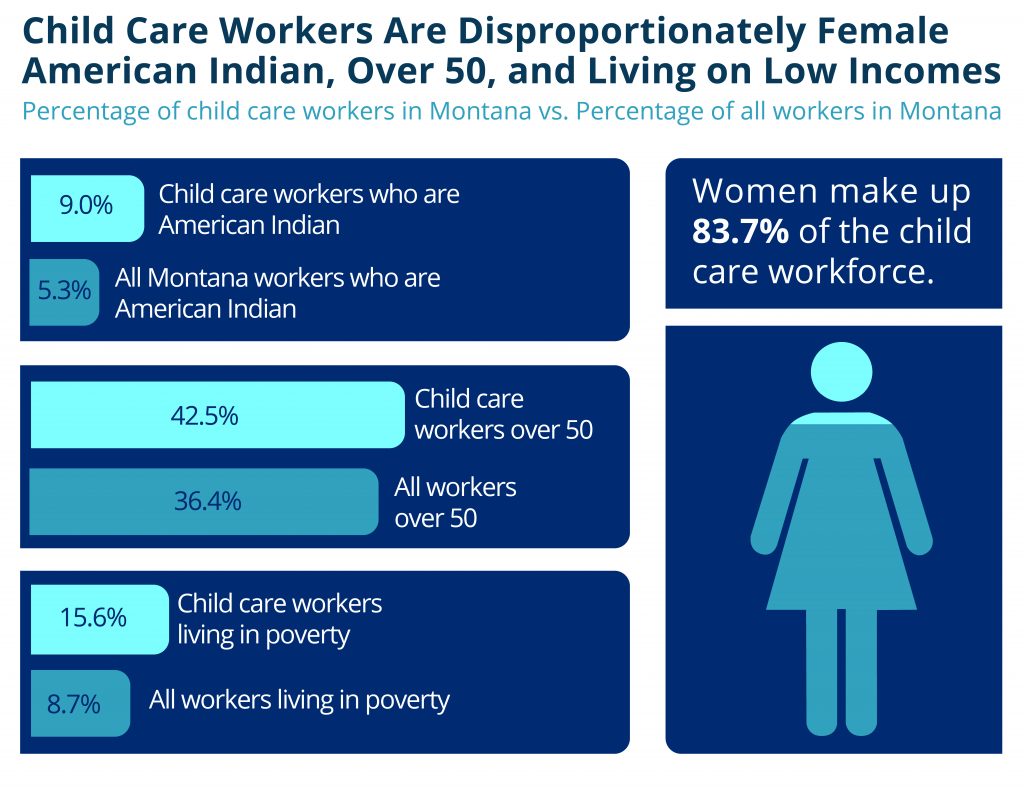

Workers in the child care industry are on the frontlines providing care for our children. Child care workers in Montana are disproportionately female, Hispanic, American Indian, over 50, and living on low incomes.[5] Montana is home to 11,300 child care and social service workers. Women make up the vast majority of this industry (83.7 percent), compared to just less than half (47.3 percent) of all Montana workers.[6] Montanans who are American Indian make up 9 percent of this industry compared to 5.3 percent of all Montana workers. Workers over 50 make up 42.5 percent of this industry, compared to 36.4 percent of all Montana workers. Lastly, child care workers are almost twice as likely than other workers to live on low incomes, with 15.6 percent of the workers in this industry earning incomes below the federal poverty level, compared to 8.7 percent of all Montana workers.

State of Child Care

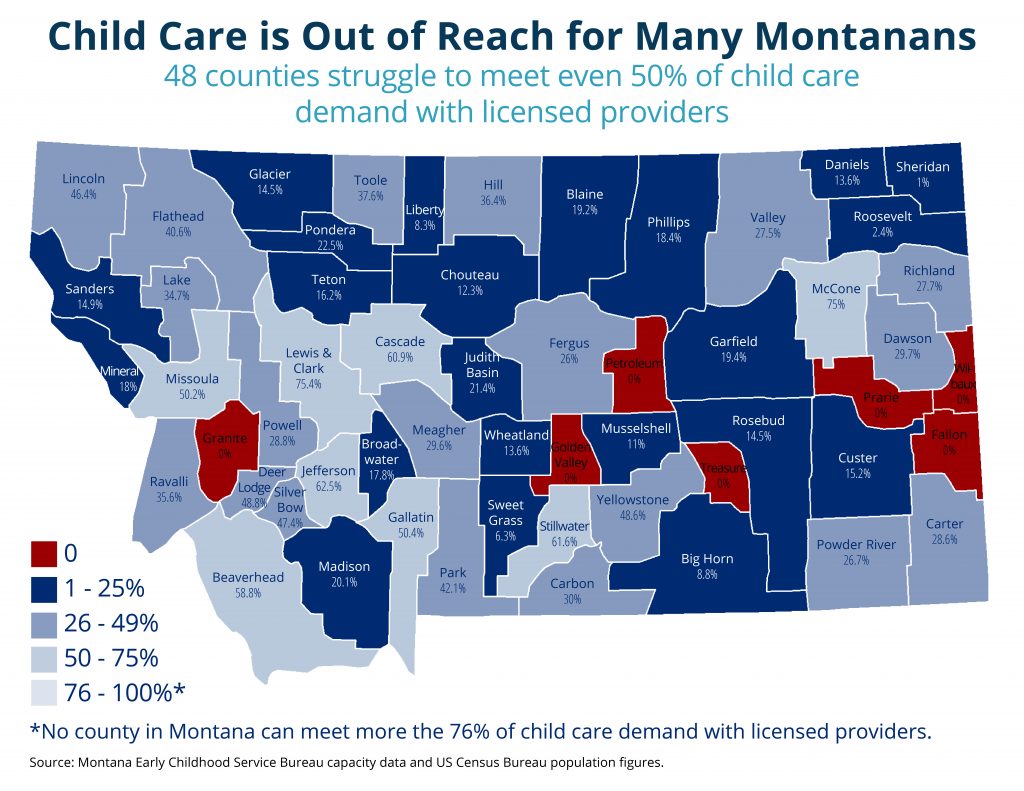

Before the coronavirus pandemic, Montana faced a lack of available child care for working families.[7] The existing child care system served less than half of Montana children needing care, and the number of providers had decreased in the previous decade.[8] The numbers of closures over the past 10 years has outpaced new openings. This is due to a number of factors such as challenges in staff retention, a lack of adequate and affordable physical space, and complexity and requirements tied to licensure. While Montana has cross-walked STARS to Quality requirements with Head Start requirements, Head Start programs can still not enter the STARS to Quality system at a given level based on program quality, as has been done in other states. Aligning these programs would streamline administration across programs and provide more consistent information for parents. [9]

American Indian families faced even greater barriers to accessing child care, with capacity to serve just one in four children in counties with high American Indian populations through licensed providers.[10] Among Montana families that were income-eligible to receive federal child care subsidies, only a quarter of those children were actually receiving subsidies, leaving thousands more children unable to access support for quality care. As a result of these inadequacies, Montana ranks 40th in the nation for child care availability.[11]

With stay-at-home orders and a reduction in employment from the coronavirus pandemic across the country, demand for child care has now dropped by 75 percent in some Montana communities.[12] Child care providers have faced a steep drop in revenue along with an increase in costs from health and safety-related needs associated with the pandemic. Nearly half of Montana families surveyed expressed concern about not being able to care for children during the COVID-19 pandemic.[13]

In Montana, 320 of the 859 licensed and registered family, group, and child care providers closed following the April 1 stay-at-home order, reducing Montana’s child care capacity by over 10,000 slots.[14] These providers need economic support to ensure they are able to reopen with the rest of the economy. Without child care, many Montanans are unable to work.

Recommendations to Support Families and Providers

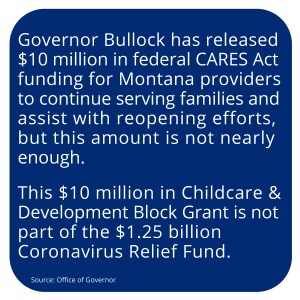

The pandemic has given Montana an opportunity to get child care back on track and provide the support working families and providers need. To begin, Montana should release $50 million of CARES Act funding. These funds would allow closed providers to retain their staff at full pay, prepare to reopen at the appropriate time, and eliminate cost burdens for families whose providers are closed. These funds would also allow open providers to offer safe, comprehensive care. Detailed recommendations follow.

Conclusions

The coronavirus public health crisis has exacerbated the underinvestment in our child care system, but it has also provided Montana with the opportunity to get it back on track. By investing in grant programs for providers, hazard pay for child care workers, and streamlining administration, Montana can move forward through the crisis.

Policymakers must also take the lessons learned during this crisis and move forward with long-lasting reforms that can make our child care system more affordable, available, and sustainable for the child care workers and the families who need care. Expanding support for parents and child care providers is a good place to start, but policymakers must also consider public pre-Kindergarten options, as Montana is one of only six states that do not fund public pre-Kindergarten.[18]

MBPC is a nonprofit organization focused on providing credible and timely research and analysis on budget, tax, and economic issues that impact low- and moderate-income Montana families.