The Montana property tax system provides support for local public services, including funding for schools, roads, and other infrastructure. Residential property owners pay almost half of all property taxes. Every two years, the state undergoes a reappraisal process to update the property values for purposes of property taxes.

Property Taxes Play a Critical Role for Schools and Local Governments

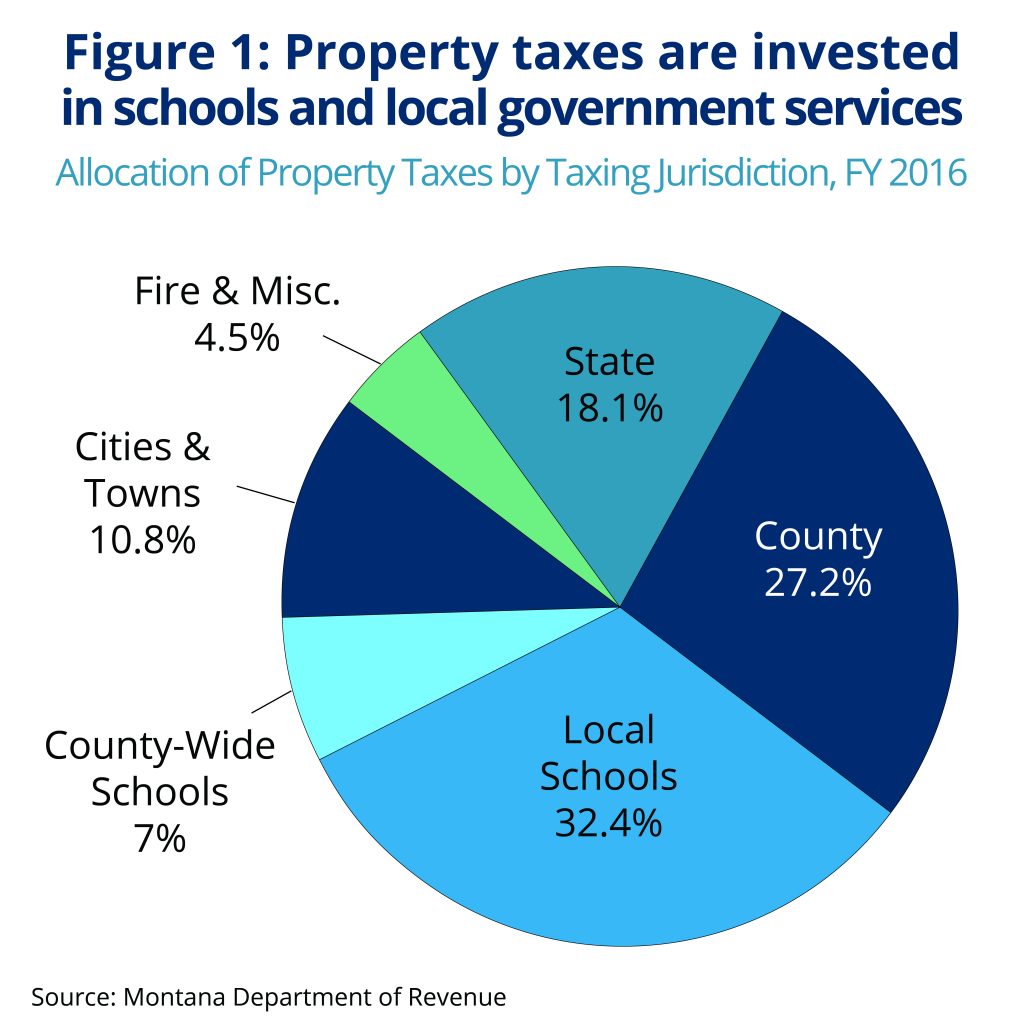

State and local property taxes collected in Montana make up approximately 37 percent of our total state and local tax revenue, for a total of $1.5 billion in 2016.[1] The vast majority of these funds are directed toward local governments and schools to invest in critical public services. Eighty-two percent of property tax revenue is invested in local governments, including supporting local schools, public safety, and infrastructure such as roads and bridges (see Figure 1).[2] The State of Montana receives about 18 percent of property taxes through statewide mills – to ensure equitable support of local schools, universities, and technical colleges.[3]

Low-Income Families Pay Greatest Share of Income in Property Taxes

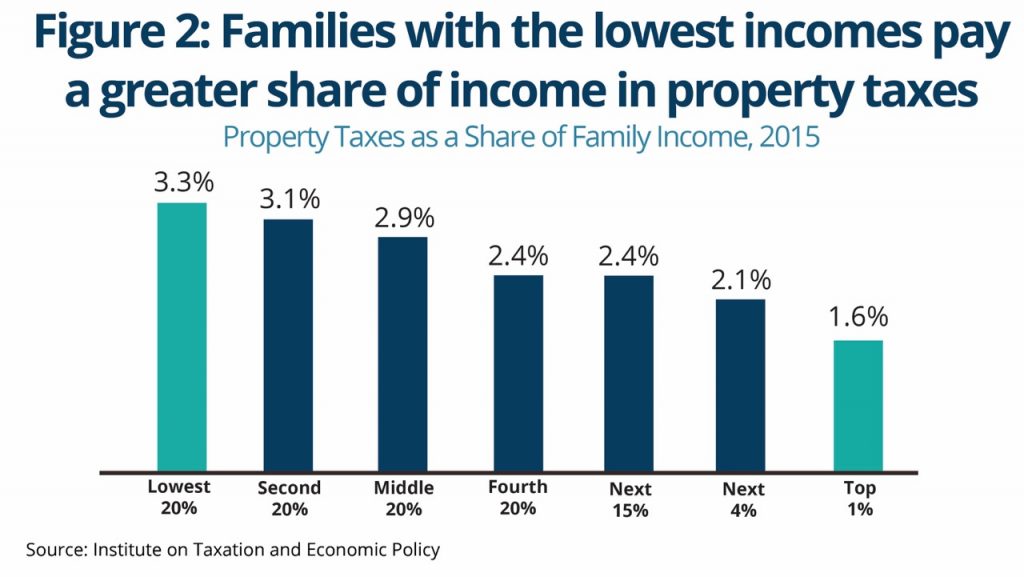

Montana homeowners pay the lion’s share of total property taxes, representing about 47 percent of all property tax revenue.[4] While property taxes are greater for homes of higher value, the property tax system is still considered regressive, meaning that on average higher-income households pay a smaller share of their income in property taxes than lower-income or middle-income households. In Montana, property taxes paid by the wealthiest one percent of taxpayers represents 1.6 percent of their overall income, compared to 3.3 percent of income for the lowest-income Montanans (see Figure 2).[5]

Property taxes tend to be regressive because they do not take into account a homeowner’s income or ability to pay, and because housing costs tend to be larger in proportion to the income of low-income households than high-income households.[6] For example, a family making $50,000 a year may own a home costing $150,000 or three times their income, while a family making $1 million per year may own a home costing $500,000, or half their income. Therefore, the property taxes paid by the low-income household will represent a greater proportion of their family income than the property taxes paid by a high-income household.

Property taxes are not limited to property owners. Renters pay a portion of the property taxes paid on rental properties because the taxes are “passed through” by the landlords when setting the rent amount. The passed-through property taxes paid by renters tend to represent a higher share of their income than for wealthy taxpayers.[7]

Both State and Local Governments Play a Role in Assessing Property Taxes

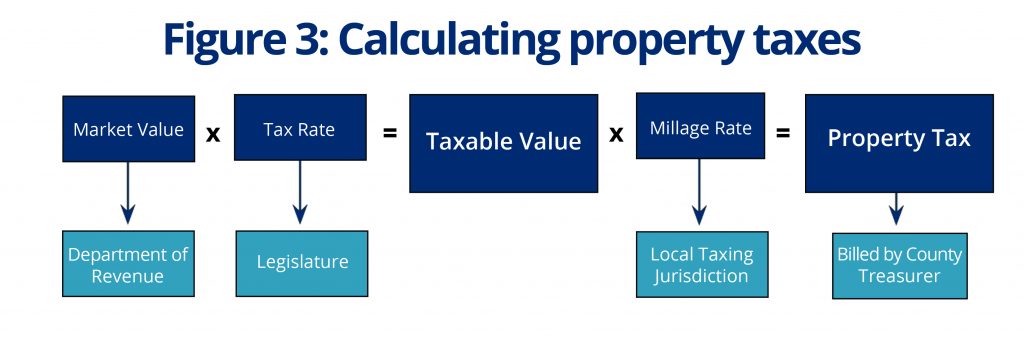

Determining what the property taxes will be on a piece of property is complicated and requires a series of steps. The Montana Department of Revenue is responsible for appraising - or valuing - property in the state to determine the market value.[8] Each taxing jurisdiction – county, city, or school district – uses these values to calculate property taxes.

A tax rate, set by the legislature, is applied to the taxable market value to determine the taxable value of the property. A mill levy is a tax rate per thousand dollars of taxable value of property. State and local mill levies are applied to the taxable value to determine the amount of property taxes owed. In total, the state imposes five different mill levies totaling 101 mills. In addition to the state mills, local cities and counties apply mill levies to the property within their jurisdiction to help fund local government operations. In 2014, an average of 560 mills were applied to all classes of property in the state.

The Montana Legislature then assigns a tax rate to each class of property and multiplies that tax rate by the property’s market value to determine the taxable value. The tax rate in 2016 for residential property was 1.35 percent, and for commercial property was 1.89 percent.[12] Local taxing jurisdictions – cities and counties – apply the mill levies to the property’s taxable value to determine taxes owed. County governments are responsible for collecting property taxes and distributing the appropriate portion of those taxes to the state, cities, school districts, and other taxing jurisdictions.[13]

Reappraisal Process Critical to Accurately Valuing Property

The Montana Constitution and state law requires the Department of Revenue to reappraise all property periodically and value similar property across the state in the same manner.[14] The reappraisal process is an important component in ensuring local governments, schools, and the state are accurately reflecting property values for property tax purposes. Over 1,400 taxing jurisdictions in the state set their budgets and mills based on these updated values. The reappraisal process formerly occurred every six years; however, tax year 2015 began the first year of a two-year appraisal cycle for residential, commercial, industrial, and agricultural property.[15] Forest land will remain on a six-year appraisal cycle.

The legislature maintained the tax rates for all classes in the 2017 session. The impact on individual homeowners depends on market values in their region or county and varies from home to home.[16]

Homeowners Pay the Greatest Share of Total Property Taxes

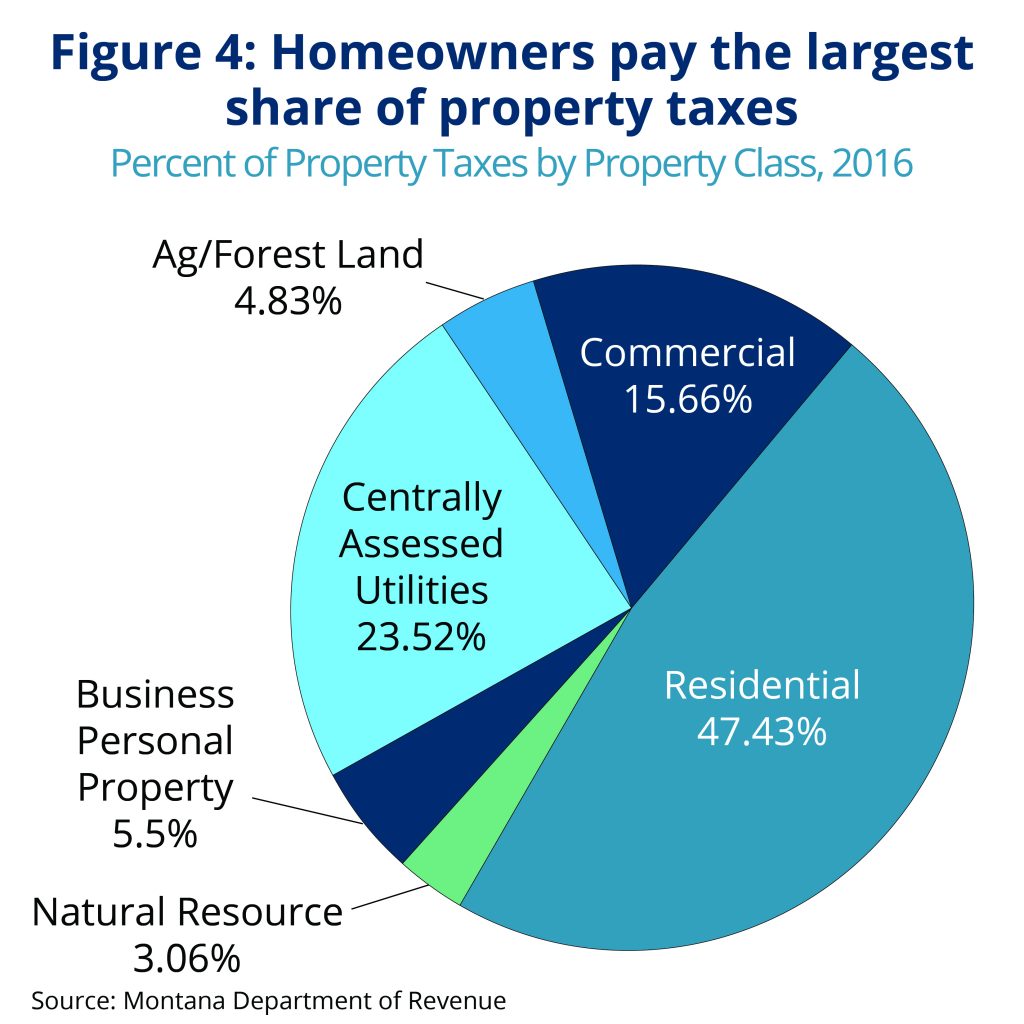

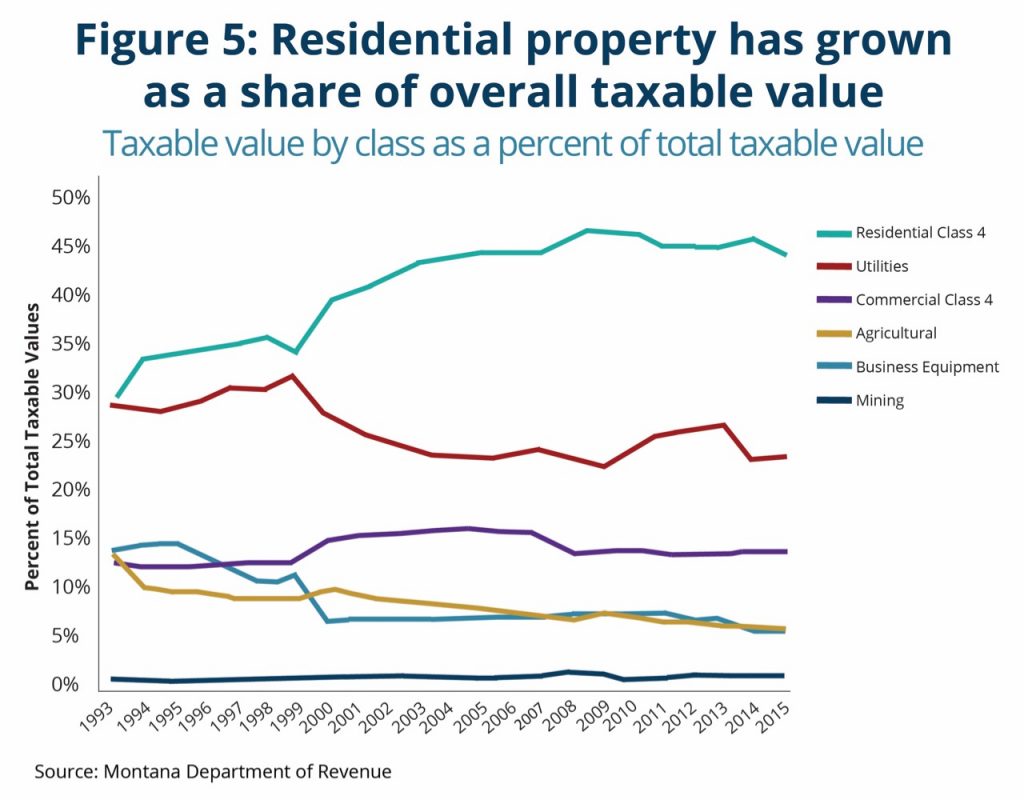

Property taxes paid by residential homeowners comprise almost half of all property taxes (see Figure 4).[17] In fact, Montana homeowners have seen an increase in the share of property taxes they pay compared to other classes of property (see Figure 5).

Residential property owners pay a greater share of property taxes, in part, because the legislature has cut the tax rates on other property classes. For example, over the past several decades the effective tax rate on business equipment has fallen by over 50 percent.[18] This often results in a shift of tax liability to other property taxpayers over time.[19] The state legislature caps the amount local governments can raise from property taxes.[20] When the legislature cuts the tax rates for some property classes, the total taxable value in the entire local jurisdiction decreases. When the taxable value goes down, so does the amount of revenue for that jurisdiction. To maintain revenue levels, the local jurisdiction would have to raise its mill levies on all property owners.[21] The increased mill levies are then applied to the remaining property in the jurisdiction, most significantly to residential property. As a result, local revenue remains constant, but the obligation to support local government functions shifts to homeowners and other property owners.

While Montana’s local governments and schools rely heavily on property tax for needed revenue, Montana’s effective tax rate for property tax is lower than the national average. Montana generates a large portion of its total taxes from property tax – 37 percent, compared to the national average of 31 percent.[22] This difference, however, is due to the fact that Montana does not have a sales tax like most other states. Nationwide, Montana ranks 31st for its effective property tax rate of 0.86 percent. The national median is 1.04 percent.[23]

Property Taxes in Indian Country

The taxation of property in Indian Country is often misconstrued as a “loss” of tax revenue. First and foremost, it should be clarified that the tax base was never “lost” as it never existed in the first place. All reservations consist of lands that tribes either reserved from their land cessions to the U.S. or lands set aside for their exclusive use via statutes and executive orders. Land owned collectively by the tribe, as well as land allotted to individual tribal members in accordance with the General Allotment Act of 1887, is called trust land and is held in trust for tribes by the federal government. Similar to all other federal property, such as national parks and forestlands, trust land cannot be taxed and is therefore not subject to state or local property taxes.[24]

As a result of the forced allotment of many reservations, there are now parcels of fee land that are privately owned and subject to state and local property taxation. This includes fee land owned by tribal members, even when their property is located on their reservation.[25]

To help offset the loss of property taxes that support local public schools, districts located on reservations and other federal lands can apply for federal Impact Aid, also known as Title VII funds.[26] Through Impact Aid, seventy-one public schools in Montana received nearly $55 million in federal aid in 2016. Fifty-nine of these schools were located on or near reservations and received almost $54 million.[27]

The State Provides Assistance for Low-Income Property Taxpayers

The Montana legislature has put in place four distinct programs to reduce property tax liability for some homeowners. The largest of these programs, the Elderly Homeowners/Renter Credit, provides taxpayers who are age 62 or older with household incomes less than $45,000 an income tax credit to help offset property taxes. The refundable credit is capped at $1,000 and phases out at incomes between $35,000 and $45,000.[28] In 2015, 12,733 Montana seniors with income tax liability received the Elderly Homeowner/Renter Credit.[29]

The state also provides two property tax programs that directly reduce property taxes for certain households. The first, the Property Tax Assistance Program (PTAP), reduces residential property taxes for low-income households. The taxpayer must live in their home for at least seven months out of the year and have incomes below $21,262 for one eligible owner (or below $28,349 for a property with two eligible owners).[30] In 2016, over 22,000 property taxpayers received assistance through PTAP, nearly a threefold increase since 2006.[31]

The state also provides the Disabled American Veterans (DAV) program which provides property tax assistance for disabled veterans. The property must be the taxpayer’s primary residence, and a taxpayer qualifies if he or she is a veteran honorably discharged and paid at the 100 percent disabled rate for a service-connected disability.[32] A spouse of a veteran who was killed while on active duty or who died from a service-connected disability may also be eligible for the DAV program. In 2016, over 2,200 veterans or family members received assistance through the Disabled American Veterans program.[33]

In 2017, the legislature created a new property tax assistance program starting in 2018 for long-time property owners where the value of their land is disproportionately higher than the value of their home.[34] The program caps the land value of their primary residence parcel to 150 percent of the improvement value, subject to a minimum per acre value consistent with the statewide average value.[35] To qualify, the owner must live in the property for at least seven months of the year and have owned (or family owned) the property for at least 30 years.

State Budget Cuts Put Strain on Property Assessment Process

The 2017 legislative session resulted in deep cuts to nearly all state agencies, including the Department of Revenue. As a result of lower revenue levels, the governor and legislature cut approximately $6 million in general fund appropriations from the Department.[36] Within the Department, the Property Assessment Division (PAD) faced the most severe cuts, with the closure of half of all county property assessment offices and significant vacancy savings.[37] While Department officials have stated their intent to continue providing services to all counties and taxpayers, there is uncertainty on how these cuts may affect the Department’s ability to accurately value all property within taxing jurisdictions.[38]

Conclusion

The Montana property tax system plays an integral role in providing support for local schools, roads, and other infrastructure. The reappraisal process ensures that the state is accurately valuing property. Property taxes tend to be regressive, taxing lower- and moderate-income households at a greater share of their income than higher-income households.

MBPC is a nonprofit organization focused on providing credible and timely research and analysis on budget, tax, and economic issues that impact low- and moderate-income Montana families.