Policy Basics is a series of background reports on issues related to the Montana budget and Montana taxes. The purpose of the Policy Basics series is to provide the public, advocates, and policy makers the tools they need to effectively engage in important fiscal policy debates that help shape the health and safety of our communities.

For generations, our tax dollars have served as shared investments in the programs and services that make our state a great place to live, work, and play. Tax dollars enable Montanans to work together to achieve things which we could not do alone - educate our children, build and maintain infrastructure, provide public safety through police and fire protection, keep our air and water clean, and pave the way to a stronger and more inclusive economy. Corporations that operate in Montana (whether they own property, pay staff, or sell products) are required to pay a tax as a percentage of their net income earned in Montana. In turn, corporations benefit greatly from our shared investments. For example, corporations hire workers educated through Montana’s public schools and colleges, utilize infrastructure like roads and water systems, and benefit from Montana’s public safety and legal system.

Montana, these shared investments are managed through the state’s “general fund.” Taxes make up the vast majority (96%) of the revenue for the General Fund, and the individual income tax is the single largest source of revenue for the general fund, comprising just over half of the state’s tax revenue (Chart 1.) [i],[ii] In general, taxes paid by corporations are paid through the corporate income tax. However, depending on how the entity is structured, business income may actually be reported through the individual income tax.

Specifically, if the business is structured as a C corporation in order to receive the legal benefits associated with such a status (including limited liability for debts and business actions and access to capital markets), its taxes would be classified as corporate taxes. All other businesses, including sole proprietorships, partnerships, limited liability corporations, and S-corporations, report income on individual returns, and this amount is reflected in both pass-through income and business income, which comprises less than 15 percent of total individual income.[iii] Taxes on business income make up just 3.5% of total income subject to individual income taxes.

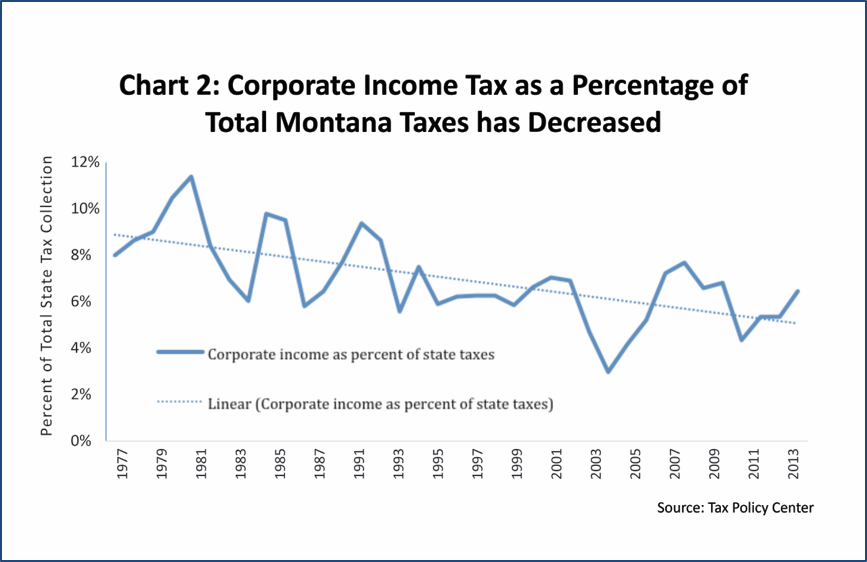

Nationally, corporate taxes as a percent of the economy have declined over the last several decades. In the 1950’s corporate taxes as a percent of the national economy averaged nearly 5%.[iv] Over the last decade, that rate has dropped to 2%.[v] Likewise in Montana, corporate taxes have been declining since the late 1970s, making up a smaller and smaller portion of total state taxes (Chart 2).[vi] In 1981, corporate income tax made up 11% of total Montana taxes, wheras in 2013 that number was down to six percent.

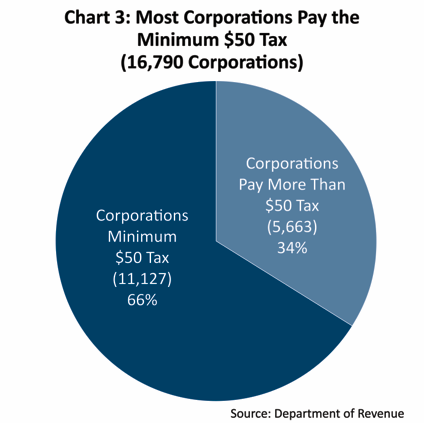

In 2012, Montana had over 16,000 C corporations, and only a third of them paid more than the $50 minimum corporate tax (Chart 3). According to Montana’s tax code, corporations pay either 6.75% of their net income earned in Montana or $50, whichever is greater.[vii] In 2012, over 11,000 (or 66 percent) of C corporations filed a return where the minimum tax was paid.

The phenomenon of corporations paying little to no state taxes has been well-documented nationally. A recent national study found that 90 profitable Fortune 500 companies paid no state income taxes in at least one year between 2008-2012.[viii] Of the 269 corporations that disclose all federal, state, and local taxes, the combined tax rate for state taxes paid was less than half of the actual average tax rate in these states.[ix]

Many profitable corporations are able to avoid paying state corporate income taxes because of:

The minimum corporate tax in Montana has been $50 since 1969.[xi] Had this tax kept up with inflation, today’s minimum amount would be $327.[xii] Updating the corporate minimum tax to account for past inflation and making sure it automatically adjusts for future inflation would modernize our tax system and slow the decline in corporate income taxes. Increasing the corporate minimum tax to $327 would raise at least $3 million in additional revenue per year.[xiii]

As costs rise for providing the basic public services, infrastructure, and education that benefit corporations, the contributions of those corporations should rise too.

Combined reporting is an important policy tool that prevents corporations from utilizing a variety of tax avoidance strategies. Montana has been a leader in this area by using combined reporting for decades. A majority of states with corporate income taxes now utilize combined reporting.[xiv]

What is Combined Reporting?

Many large companies consist of a parent company and its subsidiaries. Combined reporting requires a parent company to add its income and its subsidiaries’ incomes for the purposes of state corporate income taxes. Montana then taxes its share of the total income based on the level of activity in Montana. States without combined reporting are vulnerable to a wide array of tax avoidance strategies by corporations. The tax avoidance strategies usually involve artificially shifting profits to subsidiaries that are in states without corporate income taxes or that do not tax a specific type of subsidiary.

Combined reporting ensures that corporations pay their fair share of taxes in Montana based on their corporate activity in Montana. In addition, it improves fairness for smaller Montana-based companies. Local companies do not have subsidiaries across the country to which they can shift profits. Without combined reporting, large, multistate companies could engage in tax avoidance strategies that give them a competitive advantage over smaller, local businesses.

Outdated Tax Havens List Limits the Effectiveness of Combined Reporting

Montana requires worldwide combined reporting, which means that corporations with common ownership must report all income worldwide, unless they make a “water’s edge election.” The water’s edge election allows multinational corporations to only report their income from the United States, rather than their worldwide income. In exchange, these companies agree to pay a 7% tax rate, rather than the normal rate of 6.75%.

There are some limits to the water’s edge exclusion of international income. If a subsidiary is located in a country that is a known tax haven, the corporation may not exclude that subsidiary’s income even under the water’s edge election. In order for this exception to be useful and avoid inappropriate income shifting, the list of tax havens must be updated regularly in Montana law. The 2015 Montana Legislature failed to pass Senate Bill 167) that would have expanded the list of known tax havens and tighten other rules regarding the water’s edge election. If passed, the bill would have raised roughly $1.2 million per year and improved fairness for local companies.[xv]

The water’s edge election creates an uneven playing field for Montana-based businesses without an international presence, as it allows multinational businesses the opportunity to shift profits overseas without paying state corporate tax reflecting actual operations in the state. Tax haven abuse has grown exponentially over the past several decades, as more and more corporations have become international in scope and the industry of tax attorneys and accountants specializing in international tax planning has expanded. A recent report by Congressional Research Service estimates the overall loss of revenue to the United States as a result of offshore tax shelters at around $100 billion per year.[xvi] The number of corporations that filed a water’s edge election in Montana increased 226% from 2007 to 2012.[xvii] A proposal to eliminate the water’s edge election has been proposed in the past several sessions (Senate Bill 166 in 2015), which would raise approximately $8 million in additional revenue.[xviii]

The net operating loss carryback, a relatively obscure and costly feature of the income tax code, allows businesses experiencing an operating loss in the most recent tax year to file amended tax returns for the three previous years, deducting the current year’s loss against any profits earned in those previous years.[xix] The corporation can elect to receive a refund or apply the refund to the next year’s tax liability. Montana is one of only 17 states that still allow the net operating loss (NOL) carryback deduction.[xx] Unlike Montana, many of these states limit the amount of losses that companies can carryback.[xxi] For example, Idaho limits losses that can be carried back to $100,000 in the preceding two years. [xxii]

The NOL is particularly harmful during economic downturns. Individuals and corporations earn less during downturns and, in turn, tax revenue to the state decreases. Allowing businesses to receive a refund for previously paid taxes serves only to further compound Montana’s revenue problems during downturns. As a result, the state may struggle to fund essential public services like education, healthcare, prescription drug and child care assistance at a time when many Montanans need them the most. Eliminating the NOL carryback would bring in much-needed revenue, decrease the volatility of corporate tax revenues, and avoid unnecessary, self-inflicted fiscal damage for the state.

If the NOL carryback were eliminated, businesses could still utilize the NOL carryforward. This provision allows businesses to carry their net operating losses forward and deduct them against future profits, providing tax relief for corporations during difficult times, but not at the expense of fiscal responsibility.

Tax expenditures are often described as ‘‘silent spending.’’ They come in the form of preferences such as tax deductions, exemptions, deferrals, exclusions, credits, or lower tax rates given to individuals or businesses. Tax expenditures are considered a form of spending because they allocate funds for specific public purposes, but not through direct appropriations. These expenditures are commonly referred to as tax loopholes or incentives. They have a significant impact on state revenue as they reduce or eliminate revenue that would have otherwise been collected. Tax expenditures are not inherently good or bad policy. However, just like other state spending, they should be reviewed and evaluated on a regular basis to evaluate whether they are meeting the intended goals.

The Department of Revenue creates a report of tax expenditures each biennium. However, there is no requirement that tax expenditures are reviewed regularly by the Legislature. Corporate tax expenditures cost Montana between $11 and 16 million per year.[xxiii] For more information about tax expenditures see Montana Budget and Policy Center’s 2011 report, Flying Under the Radar: Time to Evaluate Tax Expenditures.

A Costly and Ineffective Tax Expenditure: The Domestic Production Deduction

Montana currently allows a tax break for corporations, which does nothing to promote business in the state. Montana bases its tax code on the federal tax code, meaning that deductions allowed at a federal level are automatically given at a state level unless specifically disallowed by the state. The “domestic production deduction” is a tax expenditure the federal government passed for certain activities such as filmmaking, mining, and construction that occur anywhere in the United States. However, this means that corporations receive a deduction for these activities when paying Montana state taxes, even if the production actually occurred in another part of the country.

This deduction, which has never been voted on by state lawmakers, reduced the income tax revenue to the general fund by $5.2 million in 2013. Non-residents of Montana claim the vast majority of the value of this deduction.[xxiv] For more information about the domestic production deduction, see Montana Budget and Policy Center’s 2011 report, Montana Can Bypass a Costly and Ineffective Federal Tax Break for Corporations.

All Montanans want a strong economy where small businesses can thrive, where workers can support their families, and where our children can stay in Montana and find meaningful work. To create a more inclusive and prosperous economy for future generations, we must continue to invest in our education systems, in our infrastructure, and in the health and safety of our communities. The corporate income tax is one way that we pool our resources to make sure that those investments happen. The following reforms would modernize Montana’s corporate income tax system and strengthen our ability to invest in a stronger and more inclusive economy:

MBPC is a nonprofit organization focused on providing credible and timely research and analysis on budget, tax, and economic issues that impact low- and moderate-income Montana families.