This report is the fourth of a five-part series that introduces readers to basic concepts in Indian Country. It focuses on jurisdiction and builds on the topics of sovereignty, citizenship, and land.

This report is not a comprehensive overview of jurisdiction, or the general authority of a government to exercise power over persons, property, or territory. Rather, its purpose is to provide an introduction to the complexities surrounding jurisdiction in Indian Country.

Questions about jurisdiction run central to many aspects of state-tribal relations. In fact, the first of what is today the State-Tribal Relations Committee (STRC) began its work in the late 1970s to study issues of jurisdiction.[1] The STRC is composed of state representatives and senators, with equal representation of political parties. The committee acts as a liaison with tribal governments in Montana, encourages state-tribal and local government-tribal cooperation, conducts interim studies as assigned, and may propose legislation and report its activities, findings, or recommendations to the Legislature.[2]

Decades after the STRC began its work, jurisdiction remains relevant. Economic development, for example, is closely linked to governance of land and natural resources. Determining which unit of law enforcement responds to crimes of Missing and Murdered Indigenous People depends upon the Indian status of the victim and alleged perpetrator, as well as the location of the crime. Non-tribal governments challenge the exclusive right of tribal governments to levy taxes within the jurisdictional bounds of Indian Country. While these examples are simplified, the complexities around jurisdiction in Indian Country are vast and may contribute to a delayed response, miscommunication between authorities, and policy gaps.

General Overview of Jurisdiction in Indian Country

To begin, it is important to note that tribal jurisdiction stems from the legal principle that tribal nations retain their sovereignty and nationhood status, which pre-date the establishment of the United States and include inherent powers of self-governance and self-determination.

Today, tribal governments have both civil and criminal jurisdiction. Civil jurisdiction refers to: 1) a government’s ability to regulate conduct through methods that include taxation, zoning, and traffic law enforcement; and 2) a court’s power to decide cases and impose order.[3] This area usually relates to settling disputes between private parties.[4] Criminal jurisdiction refers to a government’s ability to regulate activity by enacting and enforcing laws.[5] This area concerns a government enforcing the law related to a party’s alleged criminal behavior.

Like other governments, tribal governments use their jurisdictional authority to carry out a number of governmental activities that include education, health care, and infrastructure. The ability to exercise jurisdiction is critical for self-determination, as it allows a government to generate revenue through taxation, administer justice, conduct elections, protect the environment and natural resources, and more.

Prior to colonization, the jurisdiction of tribal nations reached far and wide. With the advancement of settler colonialism, the extent of tribal jurisdiction today is less than it was in the past. Now, a patchwork of laws govern jurisdiction in Indian Country, with federal, state, county, and tribal governments all sharing some level of jurisdictional authority. Determining who exercises that authority can be complex and depends on a number of factors that include location of the activity, citizenship status of the persons involved (i.e., tribal citizen, non-tribal citizen Indian or non-Indian), and the activity itself. Understanding these factors helps to determine whether jurisdiction is tribal, state, federal, or a combination of them.

In general, the boundaries of Indian Country define the reach of tribal authority. While Indian Country refers generally to tribal governments, communities, cultures, and peoples, it is also a legal term for the area over which the federal government and tribal nations exercise primary jurisdiction.[6] This area is where tribal sovereignty is strongest and where state authority is most limited.[7]

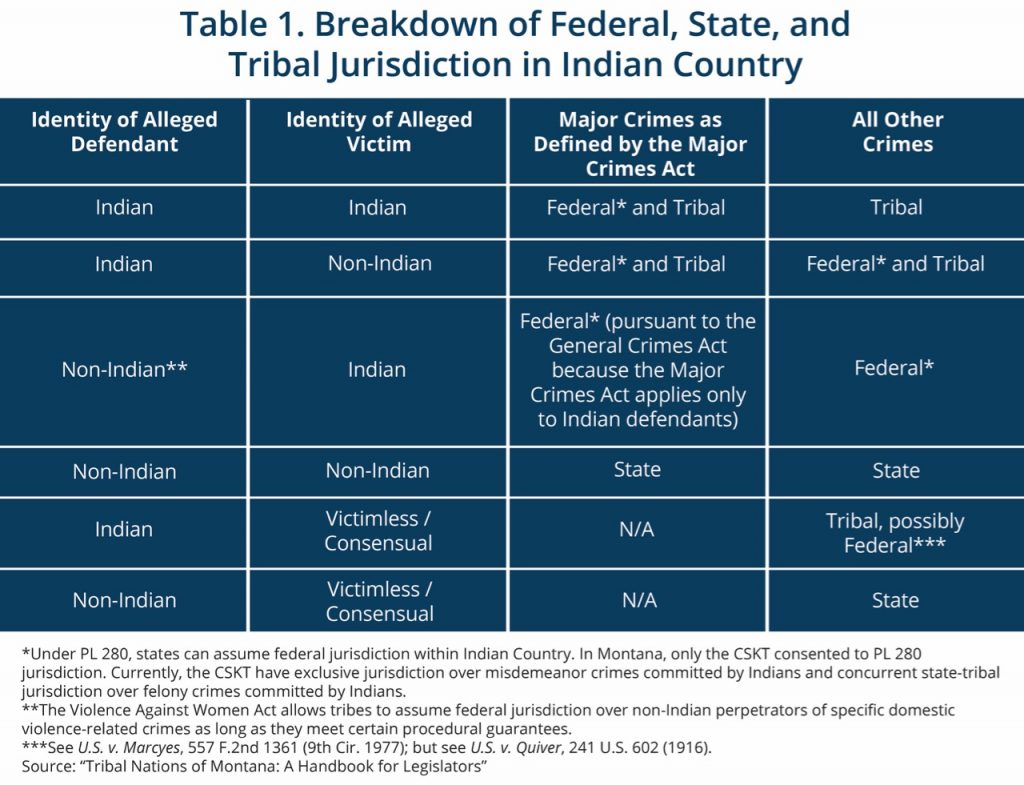

While the question of land status may seem straightforward, jurisdictional matters in Indian Country become complicated quickly. For example, tribal nations generally have civil jurisdiction over American Indians and non-Indians on tribal lands and criminal jurisdiction over American Indians on tribal lands.[8] Tribal nations generally do not have criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians. The state has jurisdiction over criminal matters in Indian Country that involve only non-Indians.[9] These complexities around jurisdiction in Indian Country can lead to confusion around who is responsible for carrying out the law and where someone should turn for help.[10] To demonstrate the complexities of jurisdiction in Indian Country, Table 1 provides an overview of criminal jurisdiction. (Questions of jurisdiction in civil law also vary and involve similar levels of complexity.)

State Jurisdiction in Indian Country

As a general principle, the federal government has ultimate power over tribal nations, which preempts the assertion of state power over tribal nations. Unless Congress delegates state jurisdiction or a federal court determines state jurisdiction exists, states do not have civil or criminal jurisdiction in Indian Country.[11] Moreover, the state cannot unilaterally pass legislation that affects jurisdiction; only Congress can do this.[12]

Issues Involving Jurisdiction

Jurisdictional considerations are at the core of many aspects of state-tribal relations. Issues range from taxation and economic development to public safety and natural resource management.

Tribal Sovereignty

Tribal lands are critical to sovereignty, or the inherent right of tribal nations to exercise self-governance and self-determination.[13] Because allotment; or the federal policy that sought to eliminate tribal sovereignty, abolish reservations, and assimilate American Indians into non-Indian society; has opened up reservation lands to non-tribal jurisdictions, including states and counties, those non-tribal jurisdictions often conflict with tribal interests and sovereignty, making it difficult for tribal nations to assert their regulatory and legal control.

Checkerboarding

Checkerboarding refers to the checkerboard-like pattern of various land types and ownerships, including by non-Indians, of reservation lands. This pattern of scattered, fractionated, and intermixed land ownership creates challenges, as different governing authorities – including state, county, federal, and tribal – claim authority to regulate, tax, or carry out various activities within reservation boundaries. Jurisdictional matters on checkerboard lands demand a high level of coordination and the development of cooperative agreements between different jurisdictions.

Taxation

Tribal self-sufficiency and self-government depend upon a tribal nation’s ability to raise revenue and regulate its territory, and the power to tax plays an essential role in this. Over time, state and local governments have successfully challenged in court tribal governments’ once-exclusive right to levy taxes within their reservation boundaries to the point that tribal taxation authority is greatly diminished today. As a result, tribal governments must provide many of the same services as other levels of government without the usual tax revenue on which other governments rely.[14]

Missing and Murdered Indigenous People

Until recently, tribal nations had no jurisdictional authority to criminally prosecute non-Indians, even for crimes committed in Indian Country. These jurisdictional gaps protected non-Indians, while compromising the safety of American Indian people. The Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2013 partially corrected this problem by providing tribal nations with special domestic violence criminal jurisdiction. However, tribal nations must meet certain conditions to exercise that authority.[15]

Of American Indian women who experience violence in their lifetime, 97 percent experience violence by non-Indian offenders.[16] Montana is among the top five states in the country for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) cases.[17] The complicated jurisdictional web is at the core of the issue, as the complexities may delay a jurisdiction’s response and contribute to a lack of resources. Missing persons investigations require a high level of coordination and resources. For missing persons located on reservation lands, in particular, those investigations can require working across multiple jurisdictions.[18]

Jurisdictional Complexities in Indian Country Demand Coordination

Because the complexities surrounding jurisdiction in Indian Country are vast and may contribute to a delayed response, miscommunication between jurisdictions, and policy gaps, jurisdictional matters demand attention and coordination.

MBPC is a nonprofit organization focused on providing credible and timely research and analysis on budget, tax, and economic issues that impact low- and moderate-income Montana families.