As detailed in MBPC’s recent report, “Criminal Justice Reinvestment in Montana: Improving Outcomes for American Indians,“ Montana is currently undertaking a significant criminal justice reform effort. Thus, this is an ideal time to consider making important changes to reduce American Indian incarceration rates. While American Indians represent approximately seven percent of Montana’s overall population, they accounted for 19 percent of all Montana Department of Justice arrests in 2015.[1] These arrests translate into disproportionately higher incarceration rates as well. In 2016, American Indians comprised 17 percent of the overall state corrections population, making up 20 percent of the state’s prison population. Here, American Indian men constituted 20 percent and American Indian woman comprised 34 percent of all inmates.[2]

Policy Recommendations:

A Brief History of Criminal Jurisdiction in Indian Country

To help provide greater background on these appallingly high rates of arrest and incarceration experienced by American Indians in Montana, this report explains some of the complexities of criminal jurisdiction in Indian Country and how American Indians can become involved in one or more overlapping justice systems depending upon the type, location, and other details of the alleged offense. This report also provides an overview of the structure of and interaction among state, federal, and tribal justice systems. Understanding these systems can help shed light on places where American Indians enter the state criminal justice system and places or ways in which state and federal/tribal collaborations might be effective in decreasing the overrepresentation of American Indians in the state criminal justice system.

It goes without saying that tribal nations across America successfully maintained public law and order in their communities for thousands of years. The traditional tribal methods of administering justice that prevailed for millennia have radically changed over the past two hundred years. Congressional action over the course of several decades to slowly but significantly shift portions of tribal authority to federal and then later state courts has driven the structure of today’s criminal justice system in Indian Country.

Due to their sovereignty, or inherent right to self-govern, American Indian tribes held sole civil and criminal authority within their territories and reservations. This changed in 1817, when Congress passed the General Crimes Act, giving federal courts jurisdiction over crimes committed by or against non-Indians in Indian Country.[3] This was later further solidified by the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Oliphant v. Suquamish Tribe in 1978.[4] In 1885, Congress passed the Major Crimes Act, which gave federal courts concurrent (or shared with tribal courts) jurisdiction over seven crimes committed by or against Indians in Indian Country.[5] This has since increased and includes: murder; manslaughter; kidnapping; maiming; sexual abuse; incest; assault with intent to commit murder; assault with a dangerous weapon; assault resulting in serious bodily injury; assault on a person under sixteen years old; felony child abuse or neglect; arson; burglary; robbery; and theft.[6]

How Sovereign Are Tribes?

As a result of tribe’s sovereign status, trying a defendant in both tribal and federal court for the same offense is not considered double jeopardy.

Source: Tribal Law and Policy Institute (2017)

While states now have sole jurisdiction over crimes involving exclusively non-Indians in Indian Country, the passage of Public Law 83-280 (PL 280) in 1953 required five, and later six, states to assume extensive concurrent civil and criminal jurisdiction in Indian Country. It also gave other states the option to take on jurisdiction.[7] As background on Congress’s actions, PL 280 was enacted during the period of federal Indian policy known as termination. This is when Congress actively sought to terminate, or end, their federal trust relationship and obligations to tribes. To that end, PL 280 resulted in “a virtual elimination of the special federal criminal justice role (and a consequent diminishment of the special relationship between Indian nations and the federal government).”[8]

Although Montana was not among the states forced to assume mandatory concurrent jurisdiction, it opted to assume PL 280 jurisdiction in 1963. At that time, only the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes (CSKT) supported the idea of concurrent criminal jurisdiction with the state, primarily because of the high costs to tribal law enforcement of policing not just tribal members, but also the majority non-Indian population living on the reservation. Almost immediately, however, the CSKT sought to end their agreement but the state would not consent. In 1993, the CSKT secured an agreement that allowed them to “reassume exclusive jurisdiction over misdemeanor crimes committed by Indians and provid[ed] for the continued concurrent state-tribal jurisdiction over felony crimes committed by Indians.” In 2017, the Montana legislature passed SB 310 at the request of the CSKT Tribal Council, creating a mechanism to allow the CSKT to withdraw from concurrent state felony jurisdiction via a tribal resolution after consulting with local government officials. The CSKT have taken no action as of yet. Sources: “Tribal Nations in Montana: A Handbook for Legislators” and “Summary of PL 280 Bills in the 2017 Session.”

From the beginning, PL 280 was controversial among tribes and states. Many tribes were upset that PL 280 was implemented without their consent or even consultation.[9] States were unhappy with being forced to assume jurisdiction without additional federal funding to support it. Both were concerned that it created confusion regarding state and tribal jurisdictions and states’ role in related civil matters.[10] PL 280 is still in effect, though Congress has since amended it to require tribal consent.

Two other pieces of federal legislation have also greatly impacted criminal jurisdiction in Indian Country. In 2010, Congress passed the Tribal Law and Order Act (TLOA) to enhance tribal authority to prosecute and punish criminals in tribal court. Specifically, TLOA aimed to recruit, train, and retain Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and tribal police officers and provide them with greater access to criminal information sharing databases. It also authorized important new guidelines for handling sexual assault and domestic violence crimes and encouraged youth alcohol and drug abuse prevention programs.[11] Additionally, it amended the 1968 Indian Civil Rights Act (ICRA) to allow tribal courts to increase fines and incarceration sentences by three times what was previously allowed under ICRA.[12]

In 2013, when Congress reauthorized the Violence Against Women Act, they included provisions to allow tribes meeting certain requirements to prosecute in tribal court non-Indian perpetrators of specific domestic violence crimes.[13]

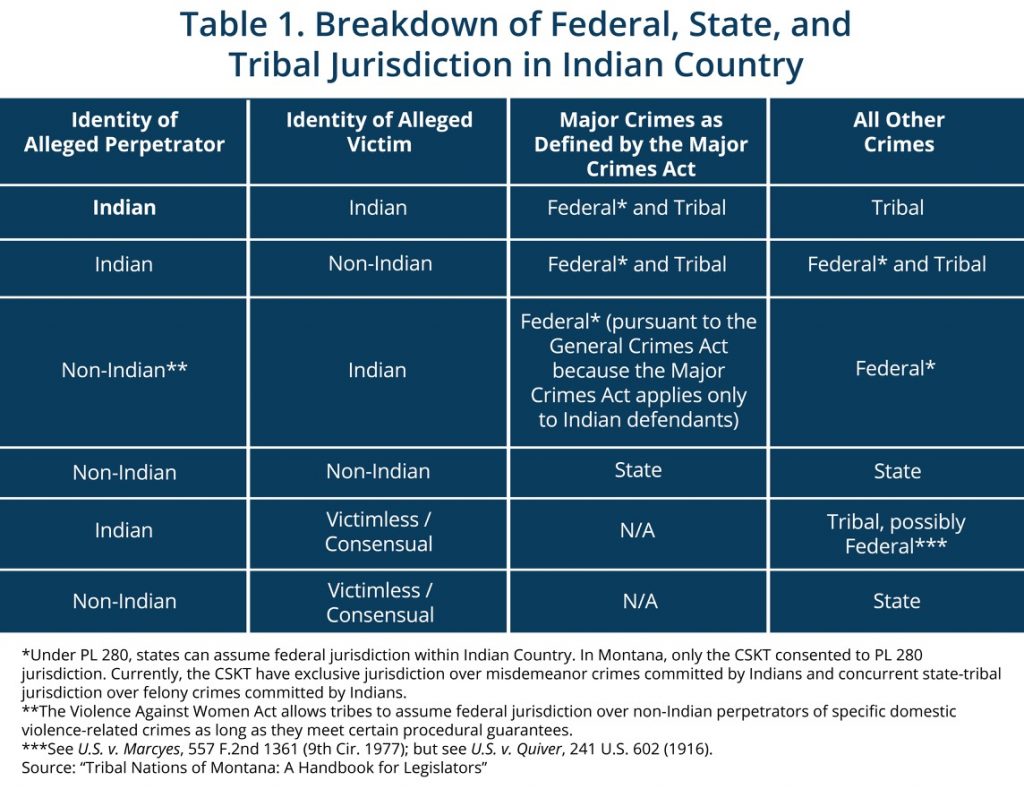

Today, in Montana, there are many different and overlapping jurisdictions, and American Indians can become involved in various justice systems depending upon the type, location, and other details of their offense, including the status of their own tribal membership as well as the identity of the victim.[14] Generally, all misdemeanor and felony crimes specified in state law committed by American Indians off-reservation fall under the jurisdiction of the state, and all other felonies/federal crimes fall under federal jurisdiction. Crimes committed on-reservation are significantly less clear-cut. Table 1 below provides a breakdown of federal, state, and tribal jurisdiction in Indian Country. Indian Country is defined in federal law as reservations and individual allotted trust land (including right-of-ways and roads) and dependent Indian communities. Indian is defined as an individual who is enrolled or recognized as Indian by a government entity and who possesses some degree of Indian blood.[15]

Federal, State, and Tribal Justice Systems in Montana

As noted above, there are many overlapping jurisdictions in Montana. There are also several associated justice systems. Like the federal and state government, each tribe has their own unique criminal laws, also known as penal codes, and their own systems for enforcing their laws. Federal, state, and tribal justice systems in Montana consist of law enforcement (sworn officers), courts and administration (judges, prosecutors, public/tribal defenders), and corrections (detention facilities, treatment, probation, and fines). Below is an overview of the structure of and interaction among these various justice systems.

Law Enforcement

Law enforcement authority in Indian Country is shared by federal, state, local, and tribal agencies.[16] Tribes retain the right to exercise criminal jurisdiction over their members and non-member Indians, as well as the right to arrest, detain, and deliver to state or federal authorities non-Indians who commit crimes on their reservations. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) investigates major crimes on all reservations with the exception of Flathead, where the state has concurrent jurisdiction over felonies. The Blackfeet, Crow, and Northern Cheyenne have delegated tribal law enforcement responsibility to the BIA. Tribes on Fort Belknap, Fort Peck, and Rock Boy’s reservations have their own tribal law enforcement officers through PL 93-638 funding and management contracts with the BIA.[17]

There are a variety of federal law enforcement agents in Montana in addition to the BIA law enforcement officers on the reservations noted above. This includes officers representing the federal Drug Enforcement Administration, Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, Board Patrol, U.S. Marshalls, and the Secret Service. In 2017, there were approximately 2,425 federal law enforcement agency employees based out of offices located across the state, serving Montana residents and providing an important link between federal and local forces.[18]

As of 2010, there were 1,956 full-time and 168 part-time sworn state law enforcement officers with arrest powers in Montana. This includes local police, county sheriffs, university police, airport security, and state agencies whose employees have the power to arrest. (These are the departments of Corrections, Justice, Fish, Wildlife and Parks, Gambling Investigation Bureau, Highway Patrol, and Transportation Motor Carriers.)[19]

Additionally, every reservation in Montana has sworn tribal or BIA law enforcement officers with arrest powers on that reservation. In 2010, the combined total for all seven reservations was 107.[20] As of 2016, Fort Peck was the only reservation in Montana that had a cross-deputization agreement with a neighboring county.[21]

Courts

In Montana, there are local, state, federal, and tribal courts. Montana has one federal bankruptcy court and one federal, or U.S. district, court (with five locations across the state). Montana is part of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, which is headquartered in San Francisco, California.[22]

State courts in Montana include 22 district courts (which can also act as appeals courts), a Supreme Court (with original and appellate jurisdiction), and specialty courts that include 22 youth courts, 26 drug courts, a water court, and a workers’ compensation court.[23]

Montana’s local courts, which are also referred to as courts of limited jurisdiction, include 81 city courts, five municipal courts, three justice courts of record, and 62 justice of the peace courts. There are also several small claims courts generally handled by justices of the peace or district courts.[24]

Across America, there are generally four types of courts in Indian Country: Code of Federal Regulations or “CFR” Courts of Indian Offenses; traditional courts; tribal courts (including intertribal courts); and tribal appeals courts.[25] Reservation courts can be very diverse and although each one enforces the particular laws of their specific tribal government, they range from adhering to more traditional dispute resolution methods to a western-style adversarial process complete with tribal bar exam requirements.

Each of the seven reservations in Montana has its own tribal court and tribal appellate court.[26] Many have additional courts including tribal constitutional, family, and juvenile courts. Each tribe also has a tribal drug court (sometimes called a wellness court), with the exception of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, which has partnered with Lake County on a drug court on the Flathead Reservation.[27]

All seven reservation-based tribal and appellate courts prosecute misdemeanor crimes committed on-reservation. Federal crimes from the Blackfeet, Fort Belknap, Fort Peck, and Rocky Boy’s reservations are prosecuted in federal district court in Great Falls. Federal crimes from the Crow and Northern Cheyenne reservations are prosecuted in federal district court in Billings.[28] As a result of their PL 280 agreement, the state of Montana has jurisdiction over felony crimes committed on the Flathead Reservation.

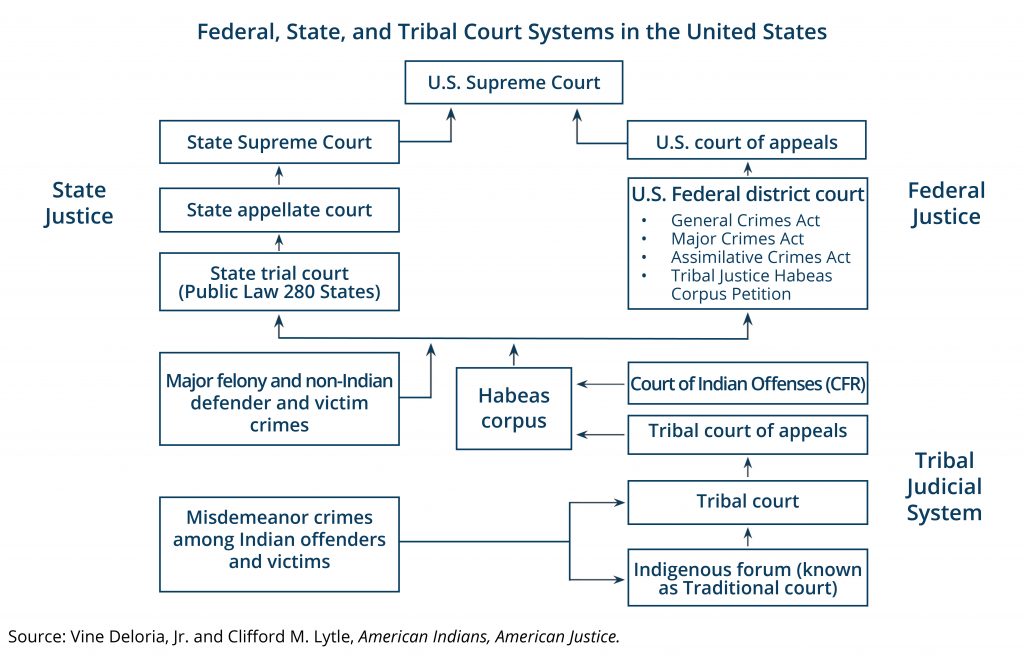

Below is a diagram showing how federal, state, and tribal court systems are structured and how they interact with one another.

Corrections

There are no federal prisons, correctional institutions, or prison camps in Montana. Federal prisoners are held in a private prison located in Shelby, Montana where 95 of the 550 beds are reserved for federal prisoners.[29] State corrections consists of both state-owned and privately-owned, contracted facilities for adults and youth. This includes five adult prisons (including the private prison in Shelby), seven pre-release centers, three youth correctional facilities, and 36 county jails.[30] State corrections also includes probation and parole (with 23 field offices and eight offices inside correctional facilities), mandatory education, fines, counseling, and substance abuse treatment, which is discussed in more detail in “Criminal Justice Reinvestment in Montana: Improving Outcomes for American Indians“ [31]

Tribal corrections consist of adult and juvenile detention facilities and transitional living centers, including at least one adult detention center on each of the seven reservations, one youth detention center on Northern Cheyenne and Fort Peck, and a solitary transitional living unit on Fort Peck. Tribal corrections also include intermediate sanctions like community service, fines, counseling, and drug and alcohol rehabilitation and treatment.[32]

Conclusion

Today in Indian Country in Montana there are many different justice systems and overlapping jurisdictions. Because of the complexity this creates it is important for policymakers and justice system employees to have a basic understanding of how American Indians can become involved in one or more of these systems. Understanding this and the ways these justice systems interact and overlap can illuminate possible entry points for American Indians and help policymakers identify places or ways in which state and federal/tribal collaborations might be effective in decreasing the overrepresentation of American Indians in the state criminal justice system.

MBPC is a nonprofit organization focused on providing credible and timely research and analysis on budget, tax, and economic issues that impact low- and moderate-income Montana families.