In today’s economy, more and more families struggle to get by on low wages and to provide resources that enable their children to succeed. Access to quality and affordable child care is one solution that enables parents to maintain stable employment and provides children with the skills they need to succeed in school and beyond.

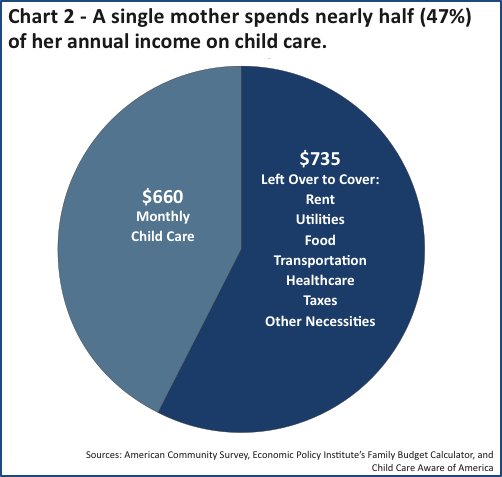

Unfortunately, affordable child care is out of reach for many working Montanans. The average cost to enroll a four year old in full-time care is $7,900 a year ($660 a month). The cost for infant care is even higher. For many Montana families, child care is the largest expense they face, and for some, child care alone can comprise half of their annual earnings. This makes it nearly impossible to pay for basic necessities or save for the future.

· Average cost of care for a four-year old is $7,900/year.

· Average cost of infant care is $9,000/year.

· Child care is considered affordable if it is less than 10 percent of total income.

· A single mother earning minimum wage spends 47 percent of her income on care for one child.

· A Montana family of three with income of $30,240 can qualify for child care assistance.

· The Best Beginnings Child Care Scholarship program offers some low-income families child care assistance.

· In 2014, the Best Beginning Scholarship program served about 4,600 children each month.

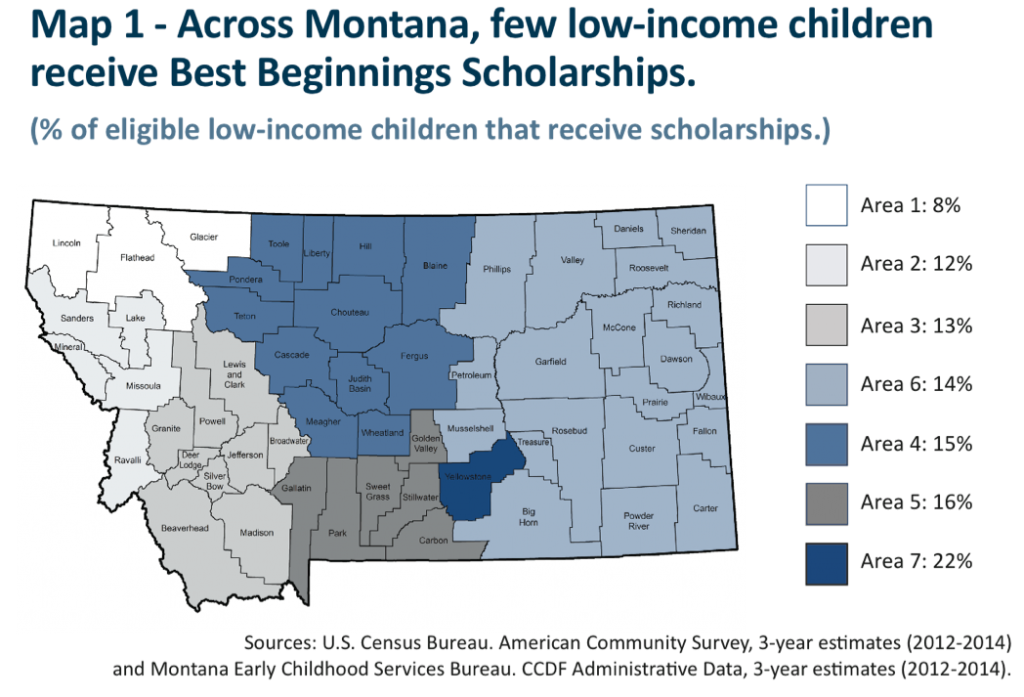

· The Best Beginnings Scholarship program serves only 14 percent of eligible low-income children.

Some low-income families in Montana can receive assistance through the state’s Best Beginnings Child Care Scholarship program to help cover child care costs. Unfortunately, because of program barriers through the state and limited funding, many families that need assistance do not receive it. In 2014, Montana’s Best Beginnings Scholarships program served just 14% of the total population of children in need. Families living in rural parts of Montana face even greater barriers to accessing child care assistance.

While recent efforts by the state have improved access to assistance, Montana can make further changes to the Best Beginnings Scholarship program to better meet the needs of low-income families by raising income eligibility limits to federally recommended levels, reforming application processes and activity requirements, and allowing individuals looking for work to apply and qualify for assistance. Additionally, greater state investments would help increase reimbursement rates to child care providers, enabling them to provide quality care services without shifting additional costs onto low-income families, or forcing them to receive lower quality care elsewhere.

U.S businesses lose up to $4.4 billion each year when employees miss work for child care needs.

When parents have access to quality and affordable child care, they know their children are in a safe place and learning skills to prepare them for school. High-quality child care helps prepare children to enter school with stronger cognitive and emotional skills and promotes better economic and health outcomes over a lifetime.[1] Additionally, access to child care can strengthen the economic security of families by helping parents maintain steady employment and supporting low-income parents who want to enter the workforce or increase work hours. For these families, parents often have to take time off work or alter their schedules because of the lack of stable care. Missing even one day of work means struggling to pay bills on time or put food on the table, not to mention the risk of job loss. Further, employers also suffer. Estimates suggest that U.S. businesses lose up to $4.4 billion each year when employees miss work for child care needs.[2]

In Montana, nearly 60 percent of families have both parents in the workforce, which means young children need safe and stimulating care environments while parents work.[3] Parents are often forced to make difficult choices between work and care, including: paying a significant portion of their income to child care, placing children in cheaper, lower-quality care, or leaving the workforce. For families working hard to build financially secure futures, these choices push them into poverty and harm their children’s opportunities to succeed.

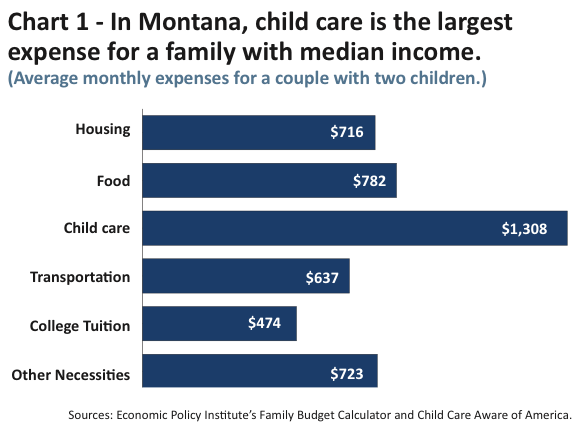

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) considers child care affordable if it consumes less than 10 percent of a family’s income.[4] However, even middle-class families spend above this affordability threshold on child care each month. For a two-parent family with median earnings ($74,340), the average cost of full-time care for two children is over $1,300 a month, 21 percent of their total income.[5],[6] In Montana, monthly child care costs exceed housing and college tuition expenses [Chart 1].[7]

Covering child care costs is a particular challenge for low-income families, especially those headed by single parents. In Montana, one in five families with children under the age of five live in poverty ($20,160 for a family of three). [8],[9] Poverty rates dramatically increase for households headed by a single-mother. One in two families with children under five and headed by a single-mother live in poverty.[10]

The steep cost of child care, combined with a low state median income, ranks Montana the 12th least affordable state for child care for families with a four-year-old.[11] For a single-mother working full-time and earning minimum wage, the cost to place her four-year old in full-time care takes up almost half – 47 percent – of her entire income [Chart 2].[12] This mom would need to contribute all of her earnings from January to June to pay for child care alone, directing limited resources away from other necessities like rent, food, health care, and transportation. This type of tough decision-making is also a problem for slightly higher earning families who do not qualify for assistance and must chose between paying a significant portion of their income to child care, placing their children in cheaper, lower-quality care, or leaving the workforce to care for their children.

For families with infants, child care is even more expensive. Child care providers who care for infants need more staff and additional training and licensing, which increases costs.[13] In 2014, the average annual cost of full-time infant care in Montana was over $9,000.[14] By HHS’s affordability metric, only 28 percent of families in Montana can afford infant care.[15]

The Child Care Development Fund (CCDF), authorized under the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG), is the primary federal funding source for state child care assistance programs.[16] States have flexibility in how they use CCDF funds and can set income eligibility guidelines, co-payment rates, and reimbursement rates. In Montana, the Early Childhood Services Bureau (ECSB) administers the Best Beginnings Child Care Scholarship program, which pays child care providers to care for some low-income children.

To qualify for scholarships, Montana families must have incomes less than 150 percent of the federal poverty line ($30,240 for a family of three) and meet activity requirements.[17] The program also requires families to pay a monthly copayment to cover a portion of the child care cost.[18] More than half of families receiving assistance pay between $25 and $50 a month in copays, but can also face additional costs.[19] Some families that receive cash assistance through the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program can also qualify for child care assistance. Further, in recognition of tribal sovereignty, Montana tribes receive CCDF funds for child care and establish their own eligibility and coverage criteria. Some families in Montana may be dually eligible for child care assistance through both state and tribal programs.[20]

Child Care and Development Block Grant Reauthorization

In November 2014, Congress reauthorized the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) for the first time since 1996. The reauthorization allows states to maintain much of the flexibility they already have, but requires them to comply with new provisions aimed at improving the health and safety of children in care and expanding access to working parents. States will need significant investments to modify their child care assistance programs without sacrificing access and quality of care for low-income families.

Montana has begun modifying its Best Beginnings Child Care Scholarship program to provide better assistance to low-income families, including:

· Expanding the eligibility period for families from 6 to 12 months.

· Extending the grace period when a parent loses employment from 30 to 90 days.

· Increasing families’ accrued absence days from seven to 24 days per calendar year.

· Proposing graduated eligibility for families with rising income up to 185 percent FPL for a period of six months.

· Allowing full-time students to be eligible without meeting work requirements.

While Best Beginnings Scholarships increase access to affordable child care, program barriers and stagnant funding make it difficult for all families who need assistance to receive it. In 2014, the year with the most recent data, an average of 3,000 Montana families received Best Beginnings Scholarships each month, providing child care assistance to an average of 4,600 children each month.[21] Unfortunately, the vast majority of low-income families who need scholarships do not receive them. Currently, over 34,000 low-income children are potentially eligible for Best Beginnings Scholarships, but only 14 percent of eligible children actually receive assistance through Best Beginnings.[22]

To better understand gaps in service, we conducted an analysis comparing the number of potentially eligible low-income children who likely need child care to the number of children that actually receive Best Beginnings Scholarships. We were unable to analyze this information at the county-level because of low population numbers in Montana. Instead, our analysis is broken out by seven Census demographic areas that each contain 100,000 people.[23] Our analysis revealed low rates of scholarship receipt across Montana, with an average of only one in seven eligible children receiving scholarships [Map 1]. The largest share of children in need who receive scholarships are in Yellowstone County, likely because of the number of child care options in and around Billings. For example, 22 percent of eligible low-income children - about 1,300 children - received Best Beginnings Scholarships in Area 7 (Yellowstone County), compared to only eight percent of eligible low-income children - 375 children - in Area 1, which encompasses Lincoln, Flathead, and Glacier counties.[24]

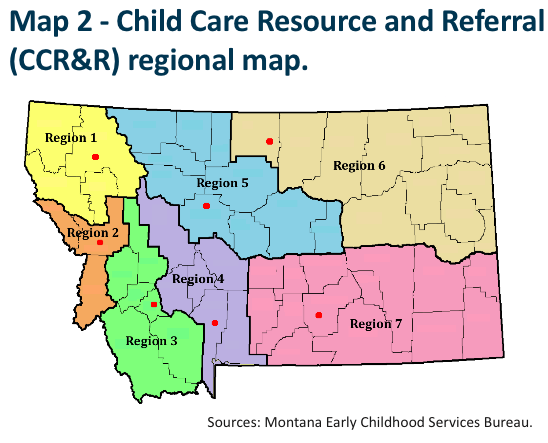

In Montana, seven centralized Child Care Resource and Referall (CCR&R) offices are located in seven regions of the state [Map 2].[25] Staff in CCR&R offices offer referral services to families looking for child care in their area and determine eligibility for Best Beginnings Scholarships. While the census areas in our analysis do not perfectly align with the seven CCR&R regions, our analysis gives a sense of Best Beginnings coverage across the regions.

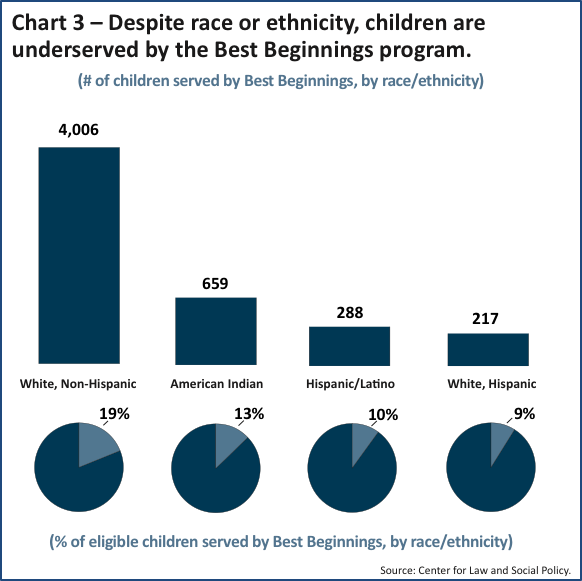

Additionally, analysis by the Center for Law and Social Policy found that the Best Beginnings Scholarship program underserves children, despite their race or ethnicity [Chart 3]. The analysis, which examined participation in Best Beginnings between 2010 and 2014, found that on average, 4,000 white children received scholarships each month during each of the five years, but only 19 percent of the total population of white and eligible low-income children received assistance. Among American Indian children, 660 received scholarships each month during the five-year period, but this enrollment comprised only 13 percent of the total eligible population of American Indian children in Montana. This statistic does not include children participating in tribal child care assistance programs. Further, the gap between children in need and children receiving scholarships was even greater among Hispanic and Latino children. Only 10 percent of eligible Hispanic and Latino children received scholarships over this five-year period.[26]

7,500 Montana families cannot afford child care on their own yet cannot qualify for assistance through Best Beginnings.

Some families earn too much to qualify for Best Beginnings Scholarships, but too little to afford child care on their own. The Child Care Development Block Grant allows states to set a maximum income eligibility limit.[27] In 2014, states like Colorado, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming set their income eligibility rates between 180 percent and 300 percent FPL. Montana, however, sets its income eligibility limit at a level that disqualifies families for child care assistance, even if they have income that is too low to afford child care on their own. A family of three must earn less than $30,240 annually (150 percent FPL) to qualify for scholarships.[28] If a family’s earnings are slightly more than the state’s eligibility threshold, they are subject to pay the entire cost of care. Currently, about 7,500 Montana families are caught in this gap, earning too much to qualify for child care assistance, but still too little to afford child care on their own.[29] By increasing Montana’s eligibility threshold to the federally recommended level, an additional 30,000 children in Montana would become eligible for Best Beginnings Scholarships.[30]

Application processes and eligibility requirements limit access. Families can apply for Best Beginnings Scholarships online or at CCR&R offices.[31] Unfortunately, many parents are denied eligibility, for reasons sometimes out of their control. In 2014, on average, almost half of the applications filed through CCR&R offices were denied.[32] While data on reasons for denial is unavailable, CCR&R and Early Childhood Services Bureau staff cite several reasons for denial.

Activity Requirements for Best Beginnings Scholarships

· Two-parent families must work at least 120 hours per month.

· Single-parent families must work at least 60 hours per month.

· Single-or two-parent families do not have to meet work requirements if all parents attend school or training full time.

· Single-or two-parent families with one or more parents attending school or training part time must meet a work requirement that takes into account education or training.

· Teen parents must attend high school or a high school equivalency program.

First, parents applying for Best Beginnings Scholarships must submit paperwork from their employers that verify employment and work schedules. This is challenging, especially for low-wage workers whose employers may not cooperate. If an employer does not cooperate or submit paperwork within a 30-day window, parents are denied assistance through no fault of their own. Second, Montana is one of only 14 states that require parents to meet child support requirements to qualify for child care assistance.[33] In 2014, 87 percent of families receiving Best Beginnings Scholarships were headed by single parents and likely went through this process.[34] Single parents who do not receive regular child support must cooperate with the state’s Child Support Enforcement Division to provide proof of child support, either through court-ordered documents or court-approved parenting plans, or prove that the absent parent has relinquished their parental rights. Some parents, who are unable to pursue child support from non-custodial parents because “cooperation is likely to result in substantial danger” to the parent or child, may submit a “good cause” waiver for not meeting requirements.[35] Parents must still provide evidence for why they cannot claim child support.[36] However, this “good cause” exemption varies by family situation. Anecdotal evidence suggests many parents choose not to apply for scholarships as a result of difficulty in meeting child support requirements. It is clear that the overwhelming amount of paperwork and processes required to apply for scholarships are large barriers to applying.

Additionally, parents may be ineligible for scholarships because they are unable to meet activity requirements. For example, a two-parent family is required to work at least 120 hours per month, about 15 hours per week per parent. In 2014, 70 percent of families receiving Best Beginnings Scholarships were working.[37] But not all working parents, especially single parents, can meet activity requirements. Many low-wage and seasonal workers have little control over their work schedules. When an employer cuts back on hours, it can cause parents to become ineligible for scholarships, again through no fault of their own.

Montana’s Early Childhood Services Bureau (ECSB) has taken several steps to improve access to assistance for low-income families. Earlier this year, ECSB changed activity requirements so that parents who are full-time students no longer have to work full-time to qualify for scholarships. Further, the state has proposed implementing a graduated eligibility policy that would allow families to continue receiving scholarships for up to 6 months, even if their income increases up to 185 percent FPL.[38] Graduating eligibility would allow 160 families in Montana to continue receiving assistance while they build financial security.[39]

Unfortunately, Montana does not allow parents searching for work to apply for scholarships. Currently, 13 states recognize “job search” as a qualifying activity for parents applying for assistance. In New Hampshire, for example, parents looking for work can apply for child care assistance and use receipt of compensation from unemployment insurance as proof of “job search” for a period of time.[40] Montana recently extended eligibility for Best Beginnings Scholarships for families that experience job loss, so that children can continue receiving care for 90 days while their parents search for work.[41] However, parents currently searching for work cannot apply for scholarships. Access to child care would support parents who need to prepare for and attend interviews and could increase their chances of securing work faster.

Investments in Montana’s Best Beginnings Scholarship program are declining. In addition to federal CCDF funds, Montana provides state matching and maintenance-of-effort (MOE) funds to administer the Best Beginnings Scholarship program. In 2014, combined federal and state funding for the program equaled $24.4 million; state dollars made up about 16 percent of total expenditures.[42] Overall funding for the program has consistently decreased over the last several years, mostly because of declining federal dollars and stagnating state dollars.[43] Between 2011 and 2014, Montana spent less than $4 million each year on its child care assistance program.[44] In comparison, tax cuts benefiting the wealthiest households and corporations have cost the state hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue, which could have been used to improve access to affordable child care and other early childhood programs.[45]

In 2015, Congress increased federal funding for CCDBG by $326 million to help states implement reauthorization requirements.[46] However, this increase accounts for less than one-third of the actual funding needed to cover costs associated with implementing reauthorization and managing caseloads. Between 2013 and 2014, 26 states increased their investment in child care assistance programs.[47] Montana should consider greater state investments to ensure that the Early Childhood Services Bureau can implement new CCDBG provisions without sacrificing families’ access to assistance.

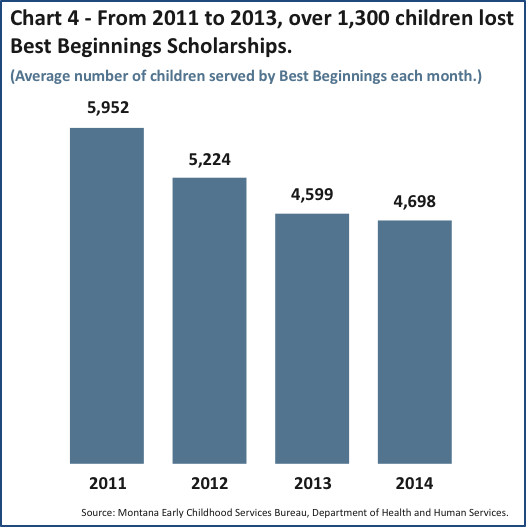

Reduced funding hinders the state’s ability to reimburse child care providers. As funding for the Best Beginnings Scholarship program consistently declined from 2011 to 2014, over 1,300 Montana children lost their scholarships [Chart 4].[48] There are likely multiple reasons for this. As mentioned earlier, parents struggle to complete applications and submit employment verification, work schedules, and child support documents. But, with declining funds, Montana cannot reimburse child care providers at an adequate rate, which hurts providers and reduces options for low-income families.

While the Best Beginnings Scholarship program pays child care providers who serve some low-income families, parents must pay a portion of child care costs through monthly copayments. Copayments begin at $10 a month and increase based on family size and income.[49] In 2014, average monthly copays comprised about 4 percent of a family’s total income.[50] However, families may pay additional costs if child care providers are not adequately reimbursed.

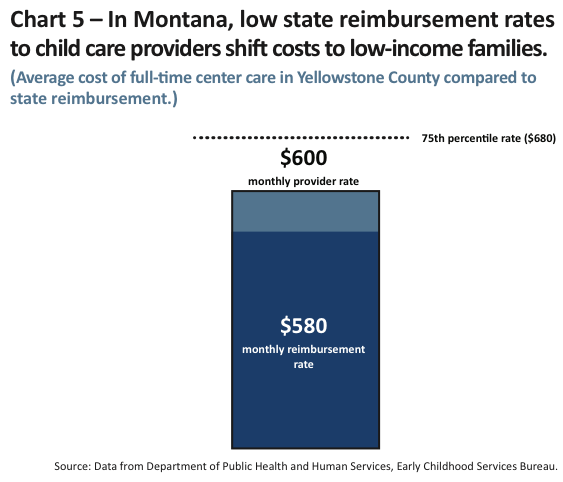

Federal recommendations suggest that states reimburse child care providers at the 75th percentile of current provider market rates so that low-income families receiving assistance can afford 75 percent of the providers in their area.[51] In Montana, reimbursement rates vary by age groups, types of care, and region, but are often below the federally recommended level.[52] In 2014, for example, the average cost of full-time center care for a four-year old in Yellowstone County was $600 a month.[53] In this case, the 75th percentile of market rate was more than the average cost of care and the state should have reimbursed providers up to $600. Yet, the state only reimbursed providers $580 per month for each Best Beginnings family served [Chart 5].[54]

When providers face a gap between what they charge and what they are reimbursed, they can shift costs onto families to make up the difference, which for Best Beginnings families, may exceed their monthly copays. For example, if a child care center – known in this example as ABC Care - served three Best Beginnings families, they would be reimbursed $580 per month, per family, but lose over $700 per year because of low reimbursement rates.[55] In this scenario, ABC Care can shift costs onto families or choose not to serve Best Beginnings families at all. If ABC Care chooses to shift costs onto families, it could mean that a single mother who receives a scholarship and pays $70 a month in copays could pay an additional $20 a month to make up for the providers loss, the equivalent of a 30 percent increase in child care costs.[56] Alternatively, when low-income families stand to pay more than their copays, they may forgo assistance altogether and place children in unlicensed care, which can mean cheaper and lower quality care for children.

Some child care providers participate in Montana’s voluntary rating system, called Stars to Quality. Participating providers signal a higher quality of care to families and can receive tiered reimbursement rates between 5 to 20 percent above the state’s standard rates, depending on the STAR level they achieve.[57] For example, if ABC Care participated in STARS to Quality, they could have been reimbursed between $609 and $696 per month for each Best Beginnings family.[58] While the Stars to Quality program represents an important step in Montana’s investment in quality child care, providers participating in the program are still not guaranteed reimbursement at the federally recommended level.

Increasing state investment into Montana’s child care assistance program could help provide resources needed to reimburse child care providers at an adequate rate that enables them to maintain their small businesses and welcome low-income families. New investment could also encourage more providers to participate in Stars to Quality, increasing options for high quality care throughout Montana.

Finally, we must also acknowledge the fact that we need greater investments in our state’s entire early childhood development system to ensure that Montana families have access to quality and affordable care and education opportunities. Several areas to consider include:

Strengthening the child care profession - child care employees are some of the lowest paid workers in the state, earning an average of $20,500 a year.[59] Despite the critical role they play in our children’s lives, child care workers struggle to get by on low-wages, rarely receive benefits like heath insurance or paid sick days, and cannot afford child care for their own children.[60] Paying child care workers fair wages and benefits and providing them access to professional development and training opportunities will enable them to thrive at work and be able to provide for their families. Doing what’s right for child care workers will also help providers attract and retain the best employees possible.

Investing in pre-kindergarten - Montana is one of only eight states that does not provide funding for statewide pre-kindergarten.[61] Creating a statewide pre-k system could help offset the child care costs that families struggle to afford, prepare children to excel in Kindergarten and beyond, and strengthen Montana’s economy by supporting working families and creating good-paying jobs in the early education industry.[62]

Improving intergration between the Best Beginnings Scholarship program and Head Start. Head Start and Early Head Start are federally funded programs that provide comprehensive care and education services to low-income families with children between 0 and 5 years old. In Montana, 29 programs serve 5,270 children throughout the state.[63] Some Head Start and Early Head Start programs are also licensed child care providers and can serve Best Beginnings families. Parents who want to enroll their children in Head Start or Early Head Start programs for child care for full-days (9.5 hours per day) must apply for Best Beginnings Scholarships through a local CCR&R office. If they qualify, the Best Beginnings Scholarship program reimburses Head Start, and Head Start covers the parent’s monthly copay. However, there are several differences between the two programs that can complicate eligibility for both programs and continuity of care.

First, activity requirements between Head Start and Best Beginnings Scholarship programs are not perfectly aligned. For example, if a parent’s employer cuts their work hours they may become ineligible for Best Beginnings Scholarships, which may affect a family’s participation in Head Start. Second, parents must balance different deadlines when applying for each program. With the overwhelming amount of paperwork that parents must submit for Best Beginnings Scholarships, some of which is out of their control, it can be challenging for parents to complete two different application processes under two different deadlines.

Finally, children enrolled in Early Head Start (ages 0 to 3) are automatically eligible to transfer into Head Start (ages 3 to 5) at the age of three. However, eligibility for Best Beginnings Scholarships is subject to change for a family during redetermination periods because of increased income or employment changes. Children’s automatic transfer from Early Head Start to Head Start conflicts with Best Beginnings’ eligibility criteria and can affect continuity of care.

Montana’s Head Start State Collaboration office and the Early Childhood Services Bureau should consider options that would better align application and eligibility processes, at least for families participating in both Head Start and Best Beginnings Scholarship programs.

Access to affordable child care helps working parents in Montana find and maintain stable employment. High-quality child care also ensures that children are in nurturing and stimulating environments that help them learn, grow, and prepare for school. While current child care costs are often out of reach for many low-and moderate-income families in Montana, some families can receive assistance through the state’s Best Beginnings Child Care Scholarship program. Unfortunately, because of application and eligibility requirements and inadequate federal and state funding, not all families who need child care assistance receive it. Program changes, like increasing eligibility limits to federally recommended levels, and significant state investments to increase reimbursement rates for child care providers would help ensure that more low-income families are able to receive assistance to pay for child care. It would also ensure that low-income families are not subject to additional costs beyond their means and enable them to access high-quality child care options in their communities.

MBPC is a nonprofit organization focused on providing credible and timely research and analysis on budget, tax, and economic issues that impact low- and moderate-income Montana families.