In 2003, the Montana Legislature passed a capital gains tax credit that benefits a very narrow portion of our population at the great expense of our collective ability to adequately invest in public programs, from education to health care. Currently, Montana is one of just nine states offering a significant tax break for capital gains income.[1] Since 2003, this tax break has proven to be unaffordable, unfair to working-class Montanans, and has not helped the economy. In fact, the tax credit costs the state tens of millions of dollars in state revenue each year and limits our collective ability to invest in schools, families, and communities across this state. These funds are especially critical now, at a time when so many families are struggling to pay rent and feed their children. It is time for the Montana Legislature to take a hard look at this costly tax break that predominantly benefits the wealthiest Montanans when those funds can be better spent on the economic recovery of our communities.

Capital gains are profits from the sale of stocks, bonds, real estate, art, antiques, or other assets. These profits are usually not taxed until they are “realized,” that is, until the asset is sold. This means that a stock or vacation home can become more and more valuable, but the investor will not pay taxes on the appreciation of that asset until it is sold. The capital gains are calculated by taking the difference between the original purchase price and the price at the time of sale. The assets owned by most Montanans like houses and retirement income are generally exempt from taxation when sold.

In 2003, the legislature passed Senate Bill 407, which created the capital gains credit and also instituted other tax cutting provisions.[2] The credit lowered the effective tax rate on capital gains by giving a nonrefundable credit starting in 2005.

Montana is one of only nine states that provide a broad tax break on income from capital gains.[3] While the federal tax code provides a lower rate on capital gains income, nearly all states require equal treatment of income from capital gains as income from wages.

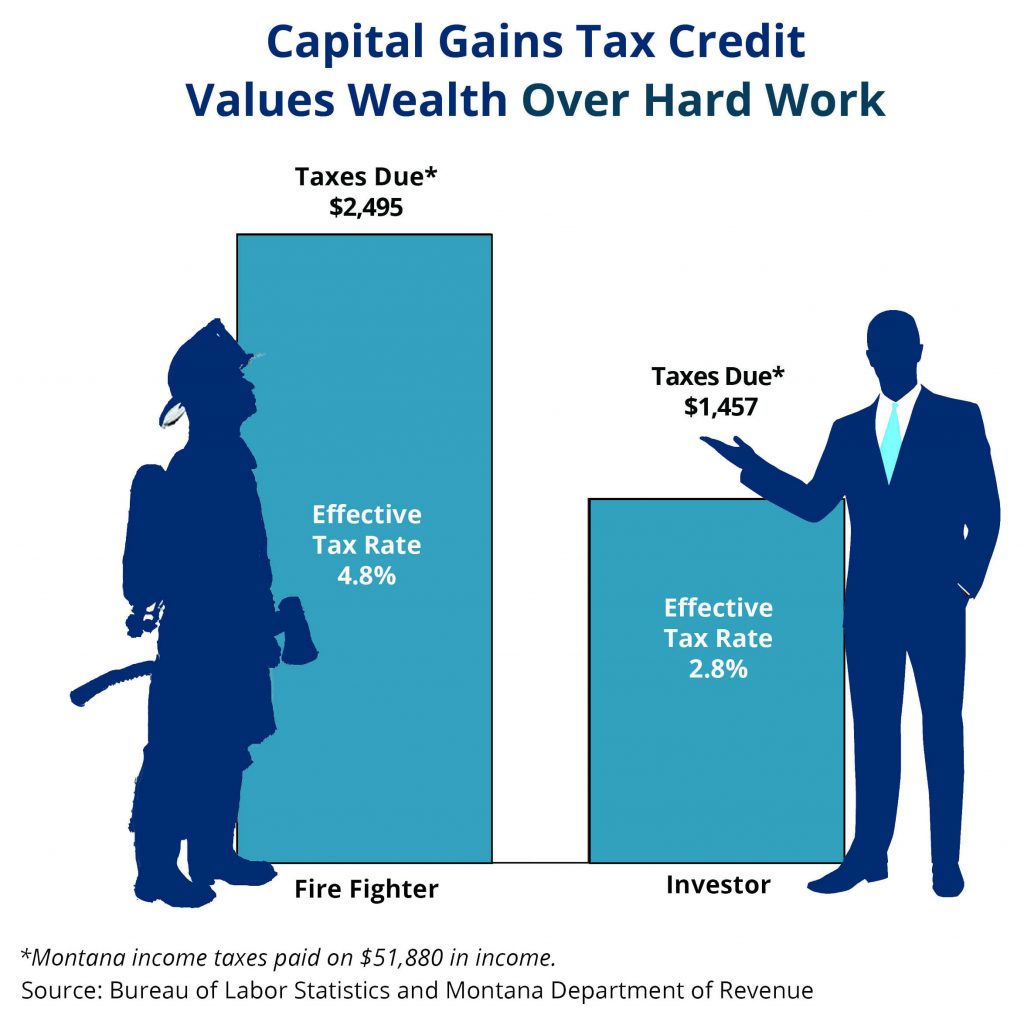

The creation of a tax break for capital gains income has created a tax system that favors wealth over work. Capital gains tax breaks mean individuals with incomes from wages pay higher tax rates than people whose income comes from growth in assets.

This chart illustrates the different taxes paid by two individuals with the same amount of income. In 2019, a firefighter in Montana earned an annual wage of $51,880.[4] Compare this to an investor who earned the same amount, but through the sale of stock. The firefighter paid $2,495 in state income taxes, and the investor paid $1,457. The investor paid $1,038, or 42 percent, less in taxes than the firefighter.[5]

Only a small number of Montanans take advantage of the capital gains credit. In 2018, 55 percent of the capital gains tax cut went to the wealthiest 4,713 taxpayers (those earning more than $420,000).[6] In 2017, over 78 percent of Montana taxpayers – more than 448,000 taxpayers – did not receive any benefit from the capital gains credit.[7] Montanans living on middle and low incomes do not benefit from the capital gain credit because they are much more likely to earn their income on the job rather than through selling large assets. Furthermore, common assets owned by most Montanans like houses and retirement funds are generally not treated as taxable capital gains when they are sold.[8] Recent analysis by the Montana Department of Revenue shows the vast majority of very wealthy taxpayers benefiting from the capital gains tax credit are taking the credit year after year (as opposed to a one-time profit).[9] The Department looked at those who had more than $1 million of capital gains income in 2010, and noted that in 2015, 82 percent of those same taxpayers were still benefiting from the capital gains tax credit.

Additionally, profits from capital gains have increased significantly since 2001. From 2001 to 2017, capital gains income by Montana taxpayers increased by almost 3 times, to nearly $2.2 billion.[10] The vast majority of those capital gains went to the wealthiest Montanans, with over half of the 2017 capital gains credit claimed by the wealthiest 1 percent of Montanans.[11] As capital gains income continues to increase for many of the wealthiest individuals, these same individuals are also reaping tax savings that others do not, all while the state loses critical revenue at a time when many families are struggling.

The capital gains credit is unaffordable – especially as our state tries to recover from a pandemic and resulting economic recession - and hurts our ability to fund services like education, health care, and infrastructure. When SB 407 passed, the legislature expected the bill to cost $26 million in 2005, the year its provisions went into effect.[12] In fact, the combined tax cuts passed in 2003 cost the state $100 million in 2005.[13] In a little more than a decade, Montana has lost approximately $976 million in revenue, from the tax cuts from 2003.[14]

A major portion of the continued revenue loss is attributed to the capital gains tax credit, primarily benefiting the wealthy. While earnings through capital gains dipped during the Great Recession, these earnings have grown significantly since 2009, representing a significant loss in revenue year after year.[15] In 2018, the state lost $55 million in revenue as a result of the capital gains tax loophole.[16] This level of revenue could have covered 4 years of public pre-K.[17]

Tax credits are an expense to the state just like any other appropriation. By giving people who sell assets like stocks and art a special tax break, the result is that the state collects less. It is also difficult for the state to predict and plan, it is impossible to control, and it benefits very few. This is in comparison to supporting public services which are more stable and benefit everyone. For example, when Montana invests in higher education, the legislature sets the amount the state contributes to universities, community colleges, and technical training centers. This helps those seeking higher incomes, businesses who need skilled employees, and our state’s economy. In contrast, the full cost of the capital gains credit to the state depends solely on individuals’ decisions to buy or sell assets, and therefore can vary greatly and is effectively unlimited.

Economic theory and experience indicate that treating capital gains more favorably than earned income does not help the economy grow and may actually prevent growth in the short-term by forcing state budget cuts.[18] In contrast, rolling back this tax break would restore revenue to help support public investments, like education, health care, and infrastructure. These funds are particularly important now as Montana navigates the pandemic and plans for economic recovery.

Montana should create a more equitable tax system by taxing wages and capital gains the same. This will create a greater incentive for businesses to invest in the creation of jobs with higher wages. The capital gains credit favors investment in capital over investment in labor, creating potential distortions in investment decisions.

In addition, Montana’s capital gains credit does not distinguish between in-state or out-of-state capital investments and therefore does not create incentives to invest in Montana. In fact, taxpayers can claim the credit when they sell the stock of a company that has never done business in our state.

While Montana’s economy has grown over the past decade, research makes it clear that this growth is not a result of tax cuts. In 2003, some legislators that supported the tax cuts for the wealthy claimed that these measures would grow the economy and result in higher revenue. This has proven to be untrue. The Montana Department of Revenue concluded, in 2013: “it is unlikely that [the 2003 tax cut] had a significant short-run stimulus effect,” stating instead that the law primarily redistributed tax obligations rather than reducing them.[19] The then-director of the Bureau of Business and Economic Research at the University of Montana stated the data on whether the tax cuts had a statistically significant impact on economic growth was “simply inconclusive.”[20]

In an analysis of the impact of the 2003 legislation, the Montana Budget & Policy Center (MBPC) measured whether the 2003 tax cuts had a statistically significant change in the actual growth in Montana’s economy by comparing measures of Montana’s economy with other states.[21] By comparing economic growth in Montana to surrounding states, MBPC found, at most, negligible evidence that the economic growth Montana experienced over the past decade could be attributed to tax cuts.[22] Instead, Montana continues to lose nearly a hundred million dollars in revenue each year that could instead be invested in our communities.

Because tax breaks on capital gains benefit a small percentage of the wealthiest households, who are more apt to keep this money than spend it in local economies, studies show very little economic impact of these tax cuts. Mark Zandi, chief economist of Moody’s Analytics has noted that efforts to provide tax cuts for capital gains income provides a very low impact on economic growth, as compared with improving policies that help families living on low and moderate incomes.[23] Dozens of highly credible economic studies around the country show that there is little connection between cuts in individual income taxes for the wealthy and economic growth in either the short or long run. States that have raised taxes on the wealthy and used that money to invest in their communities, like Minnesota, have better economies than before the tax increases and resulting investments in public education and other community needs.[24],[25] A comprehensive review conducted by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities noted that of the 15 major academic studies on income tax cuts conducted since 2000, over 75 percent found no significant economic effect of these tax cuts.[26] Since enacting the cuts, most states have actually had slower job growth than the nation as a whole and have seen their share of national employment decline.[27]

Rather than continuing the failed policy of tax cuts and resulting budget cuts, our best opportunity to support a strong economic recovery for everyone in Montana is to invest in our communities. We should strengthen support for K-12 education, expand access to post-secondary education and training, support families struggling to make ends meet, and increase good-paying jobs through investments in public infrastructure. One of the best ways we can ensure adequate state revenue and begin to properly invest in our communities is by ensuring that Montana’s wealthiest households – who have benefited from significant tax cuts both at the state level and at the federal level - pay their fair share.

In order for Montana to rebuild to a brighter future for everyone, our state needs to invest in ways that build our workforce and our economy. Our best opportunity to realize economic growth for all Montanans is through investments in our communities. There are fair and effective ways to raise the revenue needed to pay for these public investments. They include ending tax cuts and loopholes that benefit the wealthiest.

Since its passage in 2003, the capital gains credit has cost Montana hundreds of millions of dollars that could have been invested in schools, families, and communities all across this state. Only a small percentage of Montanans benefited; over half of the benefit went to the wealthiest 4,713 households. Meanwhile, the vast majority (over 78 percent) of Montana residents do not receive any benefit from this tax break and instead pay a higher effective tax rate on income from wages. Continuing preferential treatment for capital gains income is unfair to hardworking Montanans who earn their income through wages and salaries. We cannot afford such a costly credit that benefits so few households.

MBPC is a nonprofit organization focused on providing credible and timely research and analysis on budget, tax, and economic issues that impact low- and moderate-income Montana families.