The Latest Plan to Deny Assistance: Shrinking the Poverty Line

Jun 12, 2019

By MBPC Staff

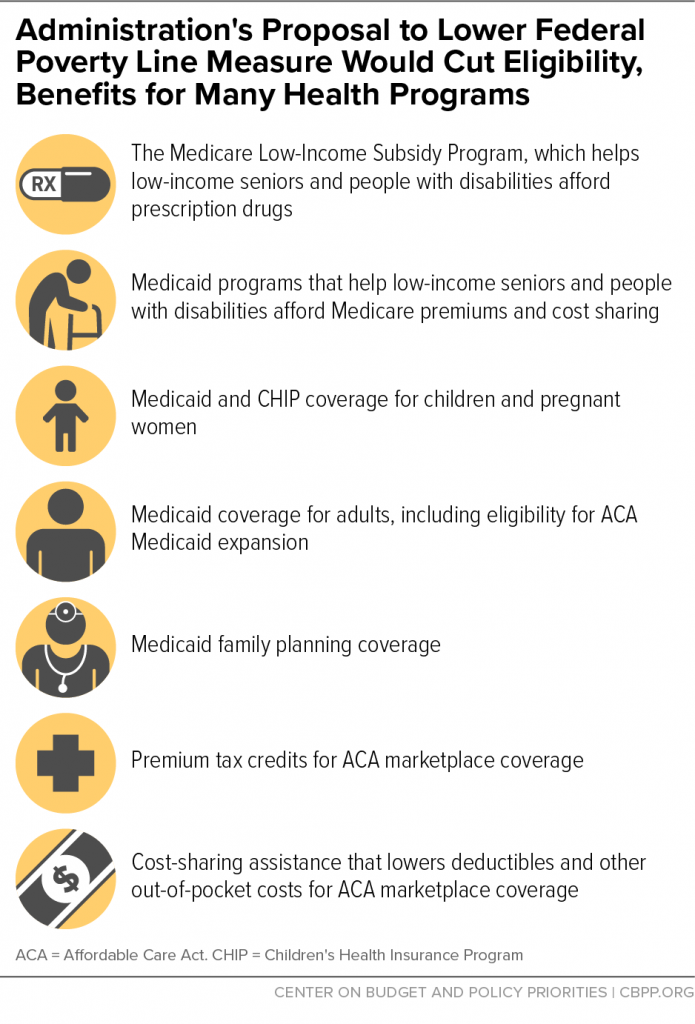

The federal administration’s proposal to lower the federal poverty line would cut benefits for most health, nutrition, and assistance programs

On May 6, the Trump Administration’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB) put out a request for comments on the possibility of adjusting how the government determines the official poverty threshold, also called the federal poverty line (FPL). That’s the calculation used to determine eligibility for a range of government social safety net programs, including Medicaid, Affordable Care Act insurance premium subsidies, SNAP and school meals, and home heating and cooling assistance. These are all determined relative to the FPL, and that measure is adjusted annually for inflation. Need a quick recap of what FPL is?

Read our Wonky Word blog.

The OMB has proposed changes to the way inflation is calculated. They propose updating the Census Bureau’s poverty thresholds using an alternative, lower measure of inflation than the traditional Consumer Price Index (known as the CPI-U) — either the “chained” CPI or the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index. This change would result in lower poverty thresholds, with the gap between the current and proposed methodology increasing each year.

How would the proposal affect people living on low- and moderate-incomes?

This is a highly wonky, technical change – and it has significant, far-reaching consequences.

Each year the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) puts out poverty guidelines, which are the basis for program eligibility and/or benefits in many health care, nutrition, and other basic assistance programs. Because the HHS poverty guidelines are based directly on the Census Bureau’s poverty thresholds, the

proposed change would lower the income-eligibility cutoffs for all of these programs, cutting or eliminating assistance to some individuals and families.

Over time this change would lead to a decrease in the number of people living in “technical” poverty,

not because they are earning more money, but because they will not meet the increasingly narrow definition of it. The Administration is effectively proposing to impose an automatic cut to eligibility, adversely affecting children living in low-income households (as well as parents, pregnant women, seniors and people with disabilities), with the magnitude of the cut becoming sharper each year.

Cuts Under the Proposal Would Increase Each Year

After 10 years, these changes would result in:

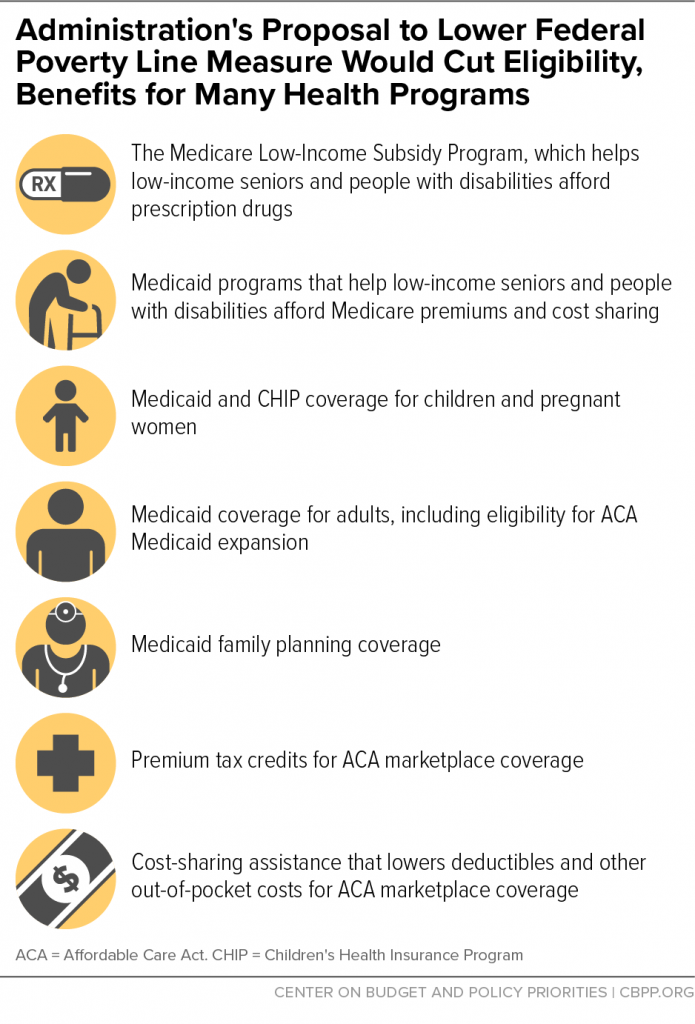

- More than 250,000 seniors and people with disabilities would lose or get less help paying prescription drug costs

- More than 300,000 children would lose Medicaid/CHIP coverage

- More than 250,000 adults would lose coverage through Medicaid expansion

- More than 150,000 individuals accessing health care coverage on the marketplace would lose cost-sharing assistance and see higher deductibles; tens of thousands would lose premium tax credits

Any attempt to measure poverty accurately needs far more than a change in the inflation adjustment; it should take into account current estimates of income and expenditures. It should also incorporate the evidence that people with incomes currently defined as above the poverty threshold still suffer considerable hardship (food insecurity, little or no savings, falling behind in rent or other bills, etc.)

The change would not make the poverty line more accurate

Any attempt to measure poverty accurately needs far more than a change in the inflation adjustment; it should take into account current estimates of income and expenditures. It should also incorporate the evidence that people with incomes currently defined as above the poverty threshold still suffer considerable hardship (food insecurity, little or no savings, falling behind in rent or other bills, etc.)

The change would not make the poverty line more accurate

- The poverty line is already below what is needed to raise a family. For example, it doesn’t take into account the full costs of families’ basic necessities, and largely excludes some necessities that have become more important in families’ budgets in recent decades like child care.

- High rates of hardship among families with incomes just above the poverty line provide more evidence of its inadequacy. The Administration proposal, by ignoring all other issues and making a single change that would further lower the poverty line, would have the opposite result of its stated intention and make the poverty line even less accurate.

- Studies suggest that costs may rise more rapidly for households with low-incomes than for the population as a whole. This means that adjusting the poverty line — meant to equal the level of income needed for families to be able to afford the basics — by a lower measure of inflation would make the poverty line more out-of-touch with families’ true expenses each year. For example:

- Households with low-income spend a larger share of their income on housing — especially rent, which has been rising faster than the overall CPI-U in recent years. The cost of rent rose 31 percent from 2008 to 2018, much faster than the overall CPI-U (17 percent).

- Low-income households may have fewer retail outlets in their neighborhood, lack access to convenient transportation, be less able to buy cheaper items in bulk, or lack internet service at home that would let them take shop cheaply online, for example. Or, in other ways, they may be less able to change their consumption patterns when relative prices change.

What’s the next step in the Administration’s process?

Currently, OMB is seeking comments on the possible change. Comments are due June 21 and can be submitted

here. It is not clear whether the Trump Administration will undertake any additional process after the comment period closes; it might simply implement a change through OMB guidance, rather than seek additional comments and issue a regulation. Comments opposing the change are important, especially from advocates and service providers. The Montana Budget & Policy Center will be submitting a comment to push back on the federal Administration’s proposal and will

post these comments to our website.

The policy’s impact would be small at first but would grow each year. For example, by the

tenth year, millions of people would lose eligibility for, or receive less help from, health and nutrition programs.

Any attempt to measure poverty accurately needs far more than a change in the inflation adjustment; it should take into account current estimates of income and expenditures. It should also incorporate the evidence that people with incomes currently defined as above the poverty threshold still suffer considerable hardship (food insecurity, little or no savings, falling behind in rent or other bills, etc.)

The change would not make the poverty line more accurate

Any attempt to measure poverty accurately needs far more than a change in the inflation adjustment; it should take into account current estimates of income and expenditures. It should also incorporate the evidence that people with incomes currently defined as above the poverty threshold still suffer considerable hardship (food insecurity, little or no savings, falling behind in rent or other bills, etc.)

The change would not make the poverty line more accurate